“Perhaps one of the mistakes in the past efforts to improve reading achievement has been the removal of struggle. As a profession, we may have made reading tasks too easy. We do not suggest that we should plan students’ failure but rather that students should be provided with opportunities to struggle and to learn about themselves as readers when they struggle, persevere, and eventually succeed.”

‘Text Complexity: Raising Rigour in Reading’, by Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey & Diane Lapp

When do you find reading hard?

Perhaps if you read the opening sentence of James Joyce’s ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ you’d experience some difficult reading:

“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.”

We can decode the words, but perhaps we are wondering whether this is a real or imagined scene? Are Eve and Adam real or are they biblical? Are you, like me, foxed by notions of ‘a commodious vicus of recirculation’? Are you interested in reading more?

Whenever we are reading a tricky text, it demands a wealth of background knowledge, well-chosen strategies, and considerable perseverance too. As expert adult readers, we recognise reading difficulty instinctively. And yet, we may struggle to describe exactly what makes reading difficult for novice pupils, or how to mediate particularly complex texts.

The answer to the challenge of reading complex texts is seldom to use simpler texts. Attempts at utilising banded books, or using reading levels or concocted text reading ages, is likely to prove problematic. If the text is simplified, then pupils don’t develop the background knowledge or strategic awareness to grapple with harder, longer texts.

We might substitute out a textbook and distil it into a few neatly arranged PowerPoint slides, but in doing so we might remove the necessary challenge to think hard about the topic. With good intent, we steal away the complex academic language our pupils need to understand and use.

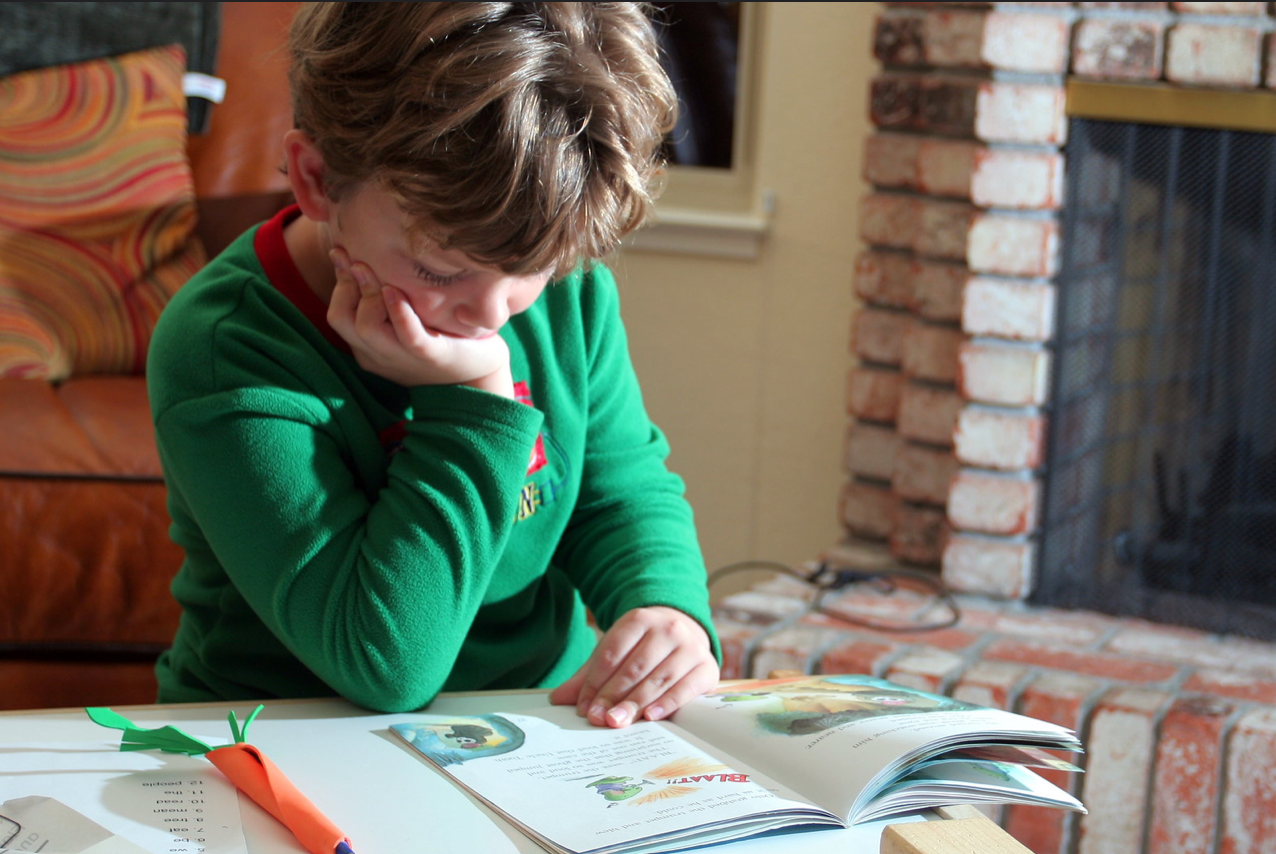

Instead of simplifying text choices, we need to appropriately scaffold complex texts. We need to support pupils to productively struggle, persevere, and ultimately experience reading success.

5 strategies to scaffold the reading of complex texts

Here are just some strategies that can best prepare pupils to read and persevere with a particularly complex text:

- Share the secret. Many pupils approach academic reading with fear and so avoid reading complex texts. It is important to let them in on the secret: they are reading hard texts, so struggling is normal. All the best readers struggle. English teachers struggle with James Joyce; historians can struggle following historical debates. Get pupils recording tricky vocabulary they don’t know, or encourage them to note as many questions as they can generate about the topic (expert readers routinely and automatically clarify and question to comprehend a complex text) in the face of this challenge.

- Stimulate curiosity. Pupils need to persevere when it comes to complex texts. Research shows that pupil interest in a topic can be an important motivator when it comes to persevering with reading very complex texts. We can help generate interest and curiosity by encouraging them to make predictions and be targeted as they read. For instance, with the Joyce opening, perhaps we can generate predictions about whether Eve and Adam is a Christian reference or not. Simple prompts can ensure pupils read actively and prove goal-focused when they read. [See this research study on generating ‘Cognitive Interest’ over ‘Emotional Interest’ with science texts’]

- Activate their prior knowledge. When pupils lack the vocabulary and background knowledge to make a text make sense, it dulls interest. It is therefore crucial to activate some prior knowledge of the topic so that pupils can more strategically cohere a sense of meaning. For example, with Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, or similar, you could start by using images of the setting – in this case Dublin. You can build a sense of place and setting (much as you would in geography), before then exploring and discussing the key themes and the unique language being used. [See my blog on ‘Academic Vocabulary and Schema Building’]

- Teach ‘keystone vocabulary’. A text is complex for a range of reasons – background knowledge, sentence length and complexity, the use of metaphorical language, and much more – but an accessible entry point is to identify key conceptual vocabulary that prove important to building comprehension. We can identify a small number of such ‘keystone vocabulary’ and teach them explicitly, offering another avenue into the text. For instance, if pupil are about to read a complex chapter on glaciation in geography, we may generate links between other keystone words like ‘abrasion’, ‘moraine’ and ‘accumulation’ and ‘ablation’. Even if pupils don’t fully know these words yet, it can prime them to recognise their importance in the chapter when they encounter them.

- Read related texts. A common complaint is that there is too little time to ‘cover’ the curriculum. And yet, if we don’t immerse pupils in complex texts, then they won’t engage in the productive struggle that makes learning truly memorable. For example, if pupils are reading a James Joyce story, then they may read an article about modernism, a short biography, and similar, as accessible entry points. If they are learning about the Great Fire of London, they might read the story, ‘Raven Boy’, along with articles offering different historical perspectives. If these texts are more accessible ‘Goldilocks texts’ (not too hard, but not too easy either), then they will open up further avenues for the topic at hand, as well as provide the productive repetition of key concepts and vocabulary in what pupils read.

[DISCLAIMER: There are innumerable strategies for reading complex texts, but this is a short blog!]

Any time a pupil is reading a complex text, it will likely prove difficult, effortful, and even frustrating. We cannot just expect to offer pupils harder and harder texts and expect them to become better readers either. However, by explicitly teaching pupils to be strategic and to cohere their knowledge and understanding, we can offer them the right tools to tackle the job of reading complex texts.

(Image via John Morgan on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/aidanmorgan/4151100524)

Comments