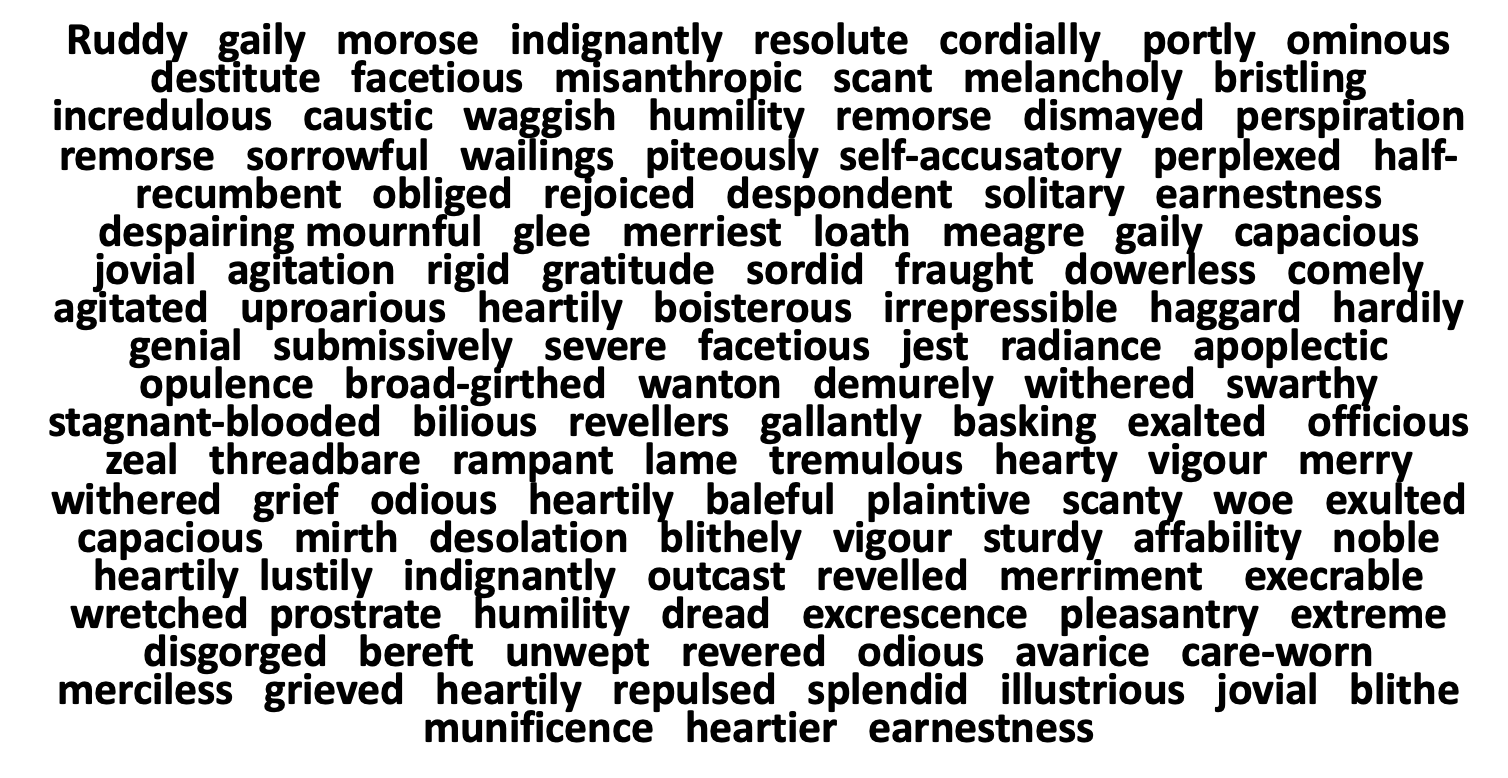

What connections can you make between these words? Are there any patterns of meaning or word families you notice? Could you even detect the author who penned these words?

These disembodied words are drawn from the Charles Dickens classic, ‘A Christmas Carol’. I have used the word cloud as a teaching tool to help students to notice, cluster and connect words with characters and themes. Of course, it is a short leap to associate these words with Scrooge, Fezziwig or Jacob Marley, and begin engaging in the brilliance of the novella more broadly.

Now, if we were to ask students to use ‘comely’ or ‘caustic’ in their own writing, we may or not see immediate success. Being exposed to words in isolation like this can be hard to translate back into context.

As Isabel Beck and colleagues state in ‘Bringing Words to Life‘: “knowing a word is not an all-or-nothing proposition: it is not the case that one either knows or does not know a word”. Recognising Dicken’s use ‘caustic’ may not see students possess the depth of word knowledge, or skill, to put it to use in their own writing.

One of the valid critiques of vocabulary instruction is that merely being exposed to a list of cloud of words (or a well-meaning knowledge organiser) does not equate to depth of word knowledge. This is a fair criticism. It should make us consider how much further exemplification, discussion and repeated exposure to rich, complex vocabulary, idioms and phrases, in reading, writing and talk, is necessary to enhance our students’ own writing.

With further exemplification, discussion, and repeated exposure (thereby building our students’ vocabulary schemata), perhaps we can see that golden thread between reading great texts and our students’ writing with a rich vocabulary strengthen and become something like an essential writing habit.

Putting words to work in writing

Charles Dickens is a consummate expert at character description, of course, with breadth of depth of vocabulary that outstrips the vast majority of expert adults. We should be wary of sharing the lexicon of an expert and expecting it to be used well by our novice students.

Without careful exemplification and guidance practice, we can end up with what Roslyn Petelin calls ‘thesaurus syndrome’. That is to say, students attempt to finds synonyms for every descriptive word in their sentences, resulting in lengthy, often clumsy applications. In English language arguments, or in history essays, they end up with a ‘purple prose’ (over-elaborate writing) that isn’t well calibrated to the task.

We know from Exeter University research charting students’ writing that older students use a more sophisticated range of vocabulary than their peers (especially in non-literary writing), but this is more nuanced that throwing the thesaurus at an essay or a piece of narrative writing.

The limits of ‘literacy across the curriculum’

Indeed, this is why generic ‘literacy across the curriculum’ can often fail. Too often, a generic solution – use dictionaries across the curriculum, or use a thesaurus to improve your writing, may actually prove counterproductive in science or geography. It may prove a well-meaning, but ineffective distraction from more nuanced and genre-appropriate improvements to subject-specific writing.

Voltaire was alleged to have said that ‘the adjective was the enemy of the noun’. In English language, a well-chosen adjective or adverb may prove essential to create skilful sentences, but then in a geography case study it could appear over-elaborate and a distraction from the human geography being described.

Funny errors can slip into our students’ writing. I recall Hamlet being described as ‘broody’ rather than ‘brooding’, with an unfortunate miscomprehension in class discussion assuming the sweet prince considering miraculous male reproduction!

With limited word knowledge, you can see students assemble a munificent verbiage… that is not always comprehensible.

Beyond ‘purple prose’ and limited word lists

Now, what I am not saying is that using and thinking hard about adjective use or synonyms is not without value. I think if you were to consider Scrooge or Hamlet that considering the subtle inferences between words like ‘melancholy’, ‘brooding’ or ‘funereal’, you can generate meaningful discussion that elicits understanding of what has been read that can then be successfully applied to our students’ writing. It just may need more careful scaffolding for subsequent application writing.

What we begin to teach is a nuanced rejection of ‘purple prose’ (writing that is too elaborate or ornate), but a recognition where a well-chosen adjective is apt and required.

It is helpful then to better calibrate the vocabulary knowledge our students need to apply words in their own writing with success. As teachers approach the challenge of teaching depth of vocabulary, it is helpful to look at Cronbach’s categories (1942) that describe increasing knowledge of words:

- Generalization: being able to define the word

- Application: selecting an appropriate use of the word

- Breadth of meaning: recalling the different meanings of the word

- Precision of meaning: applying the word correctly to all possible situations

- Availability: being able to use the word productively.

These categories help us understand that putting words to work in our students writing requires much more than simply understanding a word and being able to define it.

We can make the act of putting appropriate words to work with some explicitly vocabulary strategies:

- Simple <> Sophisticated. Too often, students don’t quite make the right choice of word because they miss the subtle register, or formality of a text. As such, being explicit about choosing between a simple and sophisticated word, over and over, can be a big help. Offering two words keeps the challenge accessible. When is ‘ask’ more apt than ‘interrogate’, or ‘sad’ more fitting than ‘crestfallen’ or ‘down in the dumps’?

- ‘Higher or lower‘. Another helpful way to explicitly help students calibrate word choices is ‘higher or lower’, with a few more synonyms or word choices. Given a range of word choices on a scale – perhaps ‘blue, sad, glum, despondent and melancholic’, you can play your cards right and go higher or lower to make the right choice. The scale

- ‘Cluster, collect, connect’. Akin to the opening word cloud, we can collate word choices and encourage pupils to cluster and connect between words. This is infinitely flexible, from words to describe a concept in geography, to a character in a Dickens novella.

My experience is that students love the challenge of experimenting with new words. And yet, we know the act of exploring, assembling and applying new vocabulary needs careful and explicit teaching, otherwise we are left with poor imitation and ‘purple prose’.

Comments