Teaching can be tremendously rewarding, but we also know the classroom can be crammed full of complexity, surprises, and problems to solve.

‘Adapting teaching’ is a recently popular – though long-standing – phrase. It captures the subtle and challenging art of teaching expertly so that pupils maximise their learning. The immense skill of effective teaching has often been described as ‘adaptive expertise’. It best describes a balance of hard-won, efficient teaching habits, along with moment-to-moment responsiveness.

We all know those situations whereby you teach a well-trodden topic, but students understand (and misunderstand) it is new ways each time. It could be the science teacher noting the experiment doesn’t generate the expected results and having to quickly translate this tricky issue and fend off any new misconceptions.

Perhaps it is the English teacher reading a set of essays on Macbeth and power that is sorely lacking meaningful analysis of the problematic representation of women. That is despite what seemed like hours of teaching… the problematic representation of women in Macbeth! Time to replan that next lesson…

It can be small misunderstandings, long-standing misconceptions, innovative new ideas, or brilliant insights from students that demands the responsiveness of ‘adaptive teaching’.

What exactly is ‘adaptive teaching’?

Lyn Corno, in ‘On Teaching Adaptively’ helpfully distinguishes ‘adaptive teaching’ and describes different types of adaptations. She describes ‘macro-adaptations’ as changes to the curriculum or grouping students differently. Then there are ‘micro-adaptations’ that form the bread of butter of teachers tweaking their plans and responding sensitively to their students.

It is the ‘micro adaptations’ which I think are key to the expert teacher and their ability to be responsive to learning. Corno neatly describes them thus:

“Practicing teachers… make micro-adaptations all the time—in the ongoing course of instruction and in response to particular students. They interpret the to and fro of class- room life, and intercede. In fact, with respect to classroom teaching, the term micro-adaptation might be defined as continually assessing and learning as one teaches—thought and action intertwined.”

Lyn Corno, ‘On Teaching Adaptively’

Adaptive teaching appears to have supplanted differentiation in the plans and minds of teachers in England. In truth, differentiation has been stained with the bad name of ‘all – most – some’ lesson objectives, along with a legion of different worksheets organised in laborious fashion. Alas, too many teachers have seen their differentiation for struggle students fail and it add to their workload too.

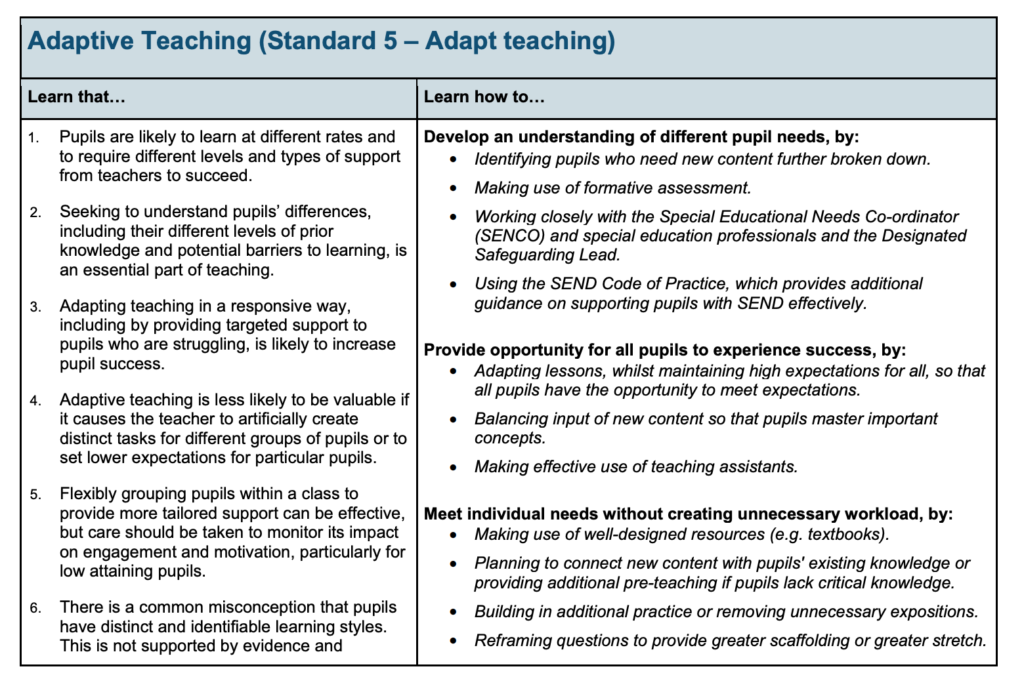

Adaptive teaching – recently enshrined in the Early Career Framework (ECF) – meanwhile, appears to better capture the nimble and necessary responses that are sensitive to a host of different responses the students generate as they grapple to understand the curriculum and develop their skills.

Adaptive teaching via vocabulary instruction

The ECF helpfully describes the common-place teaching method of ‘identifying pupils who need new content further broken down’, along with ‘planning to connect new content with pupils’ existing knowledge or providing additional pre-teaching if pupils lack critical knowledge’.

Most teachers will consider these adaptive teaching approaches to be well-served by vocabulary instruction. For example, a useful way to ‘identify students who need new content further broken down’ is to activate their prior knowledge of vocabulary. Academic vocabulary is often that unit of ‘broken down’ knowledge that proves accessible.

In English, you could be teaching a new unit of Gothic literature. Naturally, you would want to know what prior knowledge students already possess. We may also assume some cultural touchstones that could prove reference points (Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster etc.]. We might active their prior knowledge with a ‘Collage collection’ of gothic images, before asking students to generate words, phrases, and ideas they know well.

The subsequent discussion may offer up notions of Gothic monsters that need further breaking down. Most likely, we’d need to add in some additional teaching for some students who have far less experience of reading gothic texts than their peers.

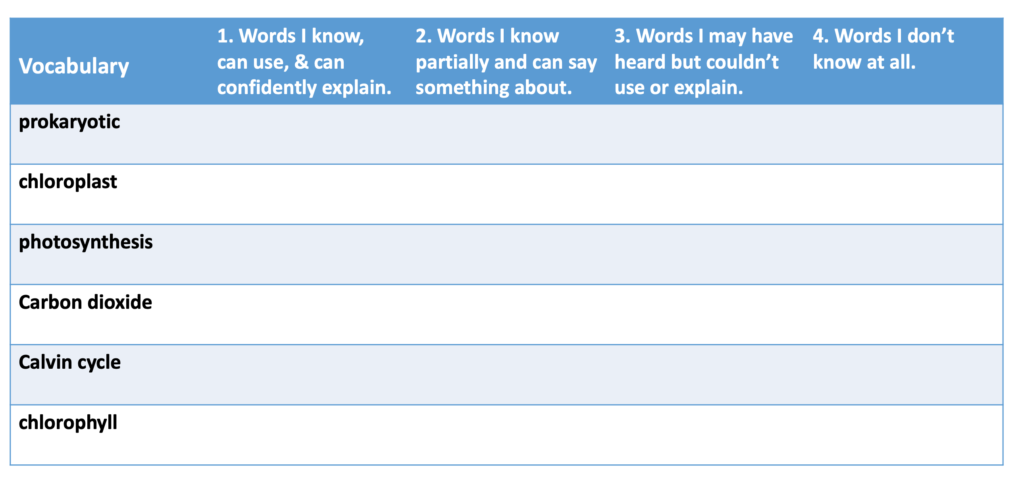

Alternatively, if we were teaching photosynthesis in science, we may begin the topic using a ‘Vocabulary diagnostic assessment’, like Dale’s word knowledge assessment:

This simple self-report vocabulary assessment can help with a familiar topic like photosynthesis to diagnose what students have remembered from previous teaching (of course, mere familiarity with vocabulary does not mean they understand this complex process, but it opens up the opportunity to diagnose what students do understand). It can result in a micro-adaptation where the terms ‘chlorophyll’ and ‘chloroplast’ are quickly retaught to a some students who need it and not others.

Vocabulary instruction lends itself neatly to ‘micro-adaptations’ because they form handy distillations of worldly knowledge that can be questioned, discussed, debated, defined, explained, and tested. They offer one route of valuable academic support so that pupils can access the curriculum, whilst being manageable units from which teachers can intelligently adapt their teaching.

Related Reading:

- Jon Eaton, from Kingsbridge Research School, has written an excellent EEF guest blog on ‘Moving from ‘Differentiation’ to ‘Adaptive Teaching’ HERE – with a brilliant free explainer on ‘Understanding Adaptive Teaching‘ resource HERE.

- Kirsten Mould has written an excellent EEF ‘adaptive teaching’ explainer blog entitled, ‘Assess, Adjust, Adapt: What does adaptive teaching mean to you‘ – HERE.

- For more vocabulary teaching strategies, my framework of ‘Three Pillars of Vocabulary Teaching‘ offers helpful strategies – HERE.

Comments