It is that time of year again. Nerves fray, students and teachers (probably parents too) as we arm our students with the obligatory revision strategies, resources, wall plans, flashcards, apps, highlighters, revision guides, and whatever else we can get our hands on, in the flimsy hope that some of it sticks.

After a decade or so of guessing when it came to revision strategies and approaches, not to mention the complex emotional mass that is the teenage brain, I have begun to build a more reliable picture from research evidence about the best strategies and methods.

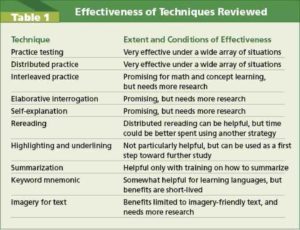

The research of John Dunlosky – see his superb ‘Strengthening the Student Toolbox‘ article – is a must read for every teacher when it comes to dispelling myths about revision and independent learning strategies. This table is a simple and powerful distillation of the research:

Now, it is all well and good consigning highlighters to the dustbin (read my diatribe on the colorful blighters here: ‘Why I Hate Highlighters!‘) and encouraging students to start practice testing and quizzing over time. And yet, what we also know is that students don’t like self-testing and don’t see it as the most effective strategy, so they continue to re-read their revision guide and highlight their notes in the privacy of their bedrooms and on kitchen tables around the land.

A solution is to train teachers, students and parents, in how these strategies work, but we also need to recognise that even when students know what strategies to apply, they are too often overconfident in their judgment of learning to use them wisely. Researchers have studied this ‘Overconfidence in children’s multi-trial judgments of learning‘, by Bridgid Finn and Janet Metcalfe. Simply being familiar with a topic can convince students they know it well: “Ah, Vectors – we revised those in our Maths revision class last week. Of course I know ’em”. This overconfidence can have a damaging knock on effect for the whole cycle of revision that our students face in the coming weeks.

We need to help our students better understand their overconfident judgements of learning. As Finn and Metcalfe show, it matters a great deal for revision and similar:

“In educational contexts students’ overconfidence in their knowledge could lead to a false confidence in the strategies that they adopted to learn the information and an underestimation of how much time they should allocate to homework or to studying for upcoming tests.”

Unlike adults, in the main, students struggle to self-regulate their learning during revision. Those students who have weaker subject knowledge and lower literacy and numeracy levels suffer from overconfidence too. Indeed, students remaining overly optimistic and confidence even after negative feedback may prove an effective psychological defense mechanism. Still, such a face-saver ultimately inhibits our students from learning, so we need to deal with the matter, but do so sensitively.

Adults are better at reining in their confidence with what is termed as ‘underconfidence with practice‘. The more we test ourselves the better we get at ‘calibrating‘ our confidence. For students, this needs explicitly pointing out and we need to verbalise and discuss their likely overconfidence when revising. It is the stuff of metacognition and self-regulation that is so integral to successful learning (see about these on the Education Endowment Foundation Toolkit HERE).

One important notion to share with students is how well they space out their self-testing, be it past exam papers, or using flashcards with key concepts or word definitions. Students need to understand that they will perform better on a test depending upon how soon they have revised the material. The true test, of course, is for them to test themselves after they have left a space of a week or more, to see how well they have transferred their knowledge into their long-term memory.

We know that from a very young age that overconfidence in learning can emerge from simple wishful thinking. One way to mitigate this is to have students working together and assessing their learning and the performance of one another. Even though we are overconfident about our own learning, we can still make accurate judgements about a peer’s performance (harsh task masters that we are!).

Calibrating student confidence

To summarise then, let’s consider some useful strategies to ensure our students are not overconfident (but not under-confident either) during their revision:

- Share with our students the evidence on the most effective revision strategies – and why they’ll be resistant to using them (re-reading and highlighting feels good and keeps them busy, whereas tests are trickier, but ultimately that deepens the learning).

- Share this information with parents and teachers, so that we can all nudge one another to apply consistent and effective approaches to revision. Like all independent learning, developing good habits that override our lazy brains is crucial.

- Talk about confidence and competence in the revision process and how they will be overconfident, quite naturally, but they should be wary of that fact.

- Train students to better ‘calibrate’ their judgements of their revision. Arranging multiple practice opportunities (seemingly ‘over learning’, even when they think they know the material at hand, is crucial here).

- Get students to work in pairs or with helpful family members when self-testing e.g. using flashcards or quizzes, so that they can be given some independent judgments on how well they low the revised material.

Comments