“There is no pleasure to me without communication: there is not so much as a sprightly thought comes into my mind that it does not grieve me to have produced alone, and that I have no one to tell it to.”

Michel de Montaigne quotes (French Philosopher and Writer. 1533-1592)

Very recently I responded to a question about great teaching with the answer that explanations, questioning and feedback were the holy trinity of teaching. I have written about questioning and feedback at length, but I have never written about teacher explanations. I thought about why and I considered that part of the problem is that explanations are so integral to everything that we do that we quickly learn our style and then explain away on autopilot pretty much for the rest of our career. I would argue that we need to reflect upon whether we are maximising the effectiveness of our explanations.

Too often we can be distracted in our planning by the tools of learning without giving the required time to the integral act of communicating our subject. When I was an NQT I went as far as scripting my explanations! I am not advocating scripting explanations by any means, it was an act borne of pure fear, but I think it important to maximise the quality of our explanations and give them our time and effort.

Looking back, some of those explanations were thoughtful and successful, perhaps more so than some of my current autopilot efforts. We are privileged because we can draw upon a wealth of knowledge gained from cognitive science, as well as our memory of great speakers and great teachers who act as role models for our practice.

These are my top tips try to address different aspects of effective explanations – the what and the how of explanations – the content and the delivery. What is reassuring is that really effective explanations can be deconstructed and be based upon evidence of how memory works, rather than being simply attributed to the power of personality. Great explanations, like all aspects of great teaching, can be repeatedly honed and improved.

Top Ten Tips:

1. ‘Know what the students know’ when planning your explanation: All great teachers have an excellent knowledge of their students. This knowledge is paramount in pitching the explanation just right. Vygotsky’s ‘zone of proximal development’ is key here – the explanation should be matched to the audience: not too complex as to be unintelligible to the students, but not too simple or unchallenging so as to bore the students and prove uninteresting. By knowing your students you can adapt your language to draw upon their prior knowledge before activating links to the new knowledge that you wish them to learn.

2. Use patterns of challenging subject specific language repeatedly:

In most explanations there are one or two key words that you want to stick in the minds of students. In my year 10 English class I am currently comparing Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnets’ with ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Subject specific words that litter my explanations repeatedly include rhetorical terms like ‘hyperbole‘ and ‘oxymorons‘. We have explored the etymology of those words, explored examples and repeatedly modelled them in our writing. With regular repetition such key words become the touchstones of effective explanations and we stress these words in our delivery for explicit emphasis.

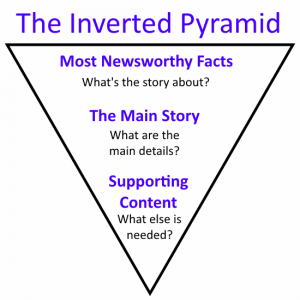

3. Make explanations simple, but not simpler. Convey a core message: I do not wish to denounce students as attention-deficit weaklings – human nature is inherently programmed to be forgetful – both adults and teenagers. Effective explanations therefore do need to have the power of compressed language. A good proverb, like “people who live in glass houses should not throw stones” has an enduring power. It generates ideas, sparks connections and combines both easily digestible language and memorable imagery – see tip 5. I would argue that most extended explanations can be compressed into such a memorable statement – what acts as the core message of our explanation. Most often this core knowledge is linked inextricably to the language of the lesson objective. A great explanation may use the ‘inverted pyramid‘, used by journalists to prioritise key information by beginning with this core message, or conversely you could use more traditional argument structures to ensure they remember what you want them to remember:

4. Engage their hearts and minds: Daniel Willingham, in his excellent neuroscience book, ‘Why Don’t Students Like School?’, outlines that emotional reactions to explanations will make them more memorable, but there are disclaimers too. We should be wary of a ‘style over substance’ performance. I like to use humour and often make jokes, but with explanations if you give a comedy routine they will likely only remember the style and the jokes, forgetting the substance of what you are saying. Getting the balance right between ensuring engagement and imparting knowledge is a delicate process: making students enjoy their learning doesn’t always translate to remembering what you want them to learn.

As most charity advertisements will attest, individual stories that spark empathy and interest prove much more memorable than mass scale problems or abstract concepts. Emotional and personal stories are memorable: I remember very little about GCSE Chemistry except the emotive story of Marie Curie. We need to use examples that hook in their hearts and mind onto the knowledge we want them to remember in the long term. To summarise: use humour carefully; use interesting stories about individuals to engage their empathy (something proven to be a natural physical and emotional response when reading stories); link to their personal interests but ensure you return relentlessly to the core message.

5. ‘Paint the picture’ – use analogies, metaphors and images: Cognitive science has proven that analogies and metaphors are crucial to language, thinking and memorising knowledge (see here). Our minds naturally draw upon ‘schemas‘ – a psychology term to define the existing patterns of knowledge we have to help us learn new knowledge. A key way of making new knowledge memorable to to hook it into existing ‘schemas‘. For example, if we were given something to eat we have never eaten before then we would draw upon our prior knowledge – ‘this tastes like chicken!’. They give students helpful templates to build on their prior knowledge and allow them to make educated guesses. When exploring the term ‘oxymoron’ with my English class we drew upon our knowledge of the term ‘moron’, then compared and contrasted this label with the character of Romeo. In Maths, teachers consistently draw upon real world ‘schemas’ to make concepts memorable. By using imagery and metaphors that evoke mental images, students can make mental hooks into what they already know and better organise their new knowledge.

6. Tell compelling stories: Daniel Wllingham describes stories as being “psychologically privileged” in the human mind and memory. As an English teacher this strikes at the heart of what I believe about emotion, memory and learning. Memorable personal stories brings History and facts alive; dry statistics become enlivened when in the context of a story. 64% of students achieving A grades in exams is interesting, but not nearly as memorable as stories of individual students toiling and overcomes tough circumstances to gain an A grade. Our minds make meaning by creating stories. With History we imagine and empathise with particular ‘characters’. Our hearts and minds are captured when a ‘conflict‘ is posed involving characters. Our explanations therefore need to be built like narratives: with characters, conflicts and resolutions. We must avoid meaningless anecdotes of course, as stories should serve to illuminate the core message and not prove a distraction.

7. Make abstract concepts concrete and real: Akin to story making and using effective imagery and analogies to illuminate information, we better remember concrete knowledge rather than abstractions. We are hardwired to do this. From birth, our first words are invariably concrete nouns and verbs to articulate our most basic of needs. Hopefully you have remembered the proverb used in tip 3: “people who live in glass houses should not throw stones“! This is a great example of an abstract idea being made concrete and memorable. We must also avoid using too much abstract language and jargon beyond the patterns of key subject specific language we want students explicitly to remember – see tip 2 – otherwise we risk losing the core message we want students to remember.

Brian Cox, the scientist and television personality (yes – I have noticed he isn’t a teacher and some television personalities have proven to be notoriously bad teachers!) is a great example of someone who makes abstract scientific concepts concrete to good explanatory effect. His explanations illuminates a topic for someone like me who has little sophisticated knowledge of science (the typical student!) in a concrete and memorable way. This short video is a great example of a successful explanation that ticks off many points from my tips with aplomb:

8. Hone your tone: Of course, the delivery of explanations carry a great deal of weight if we are to make them truly memorable. Charisma without content is vacuous, but content without clarity and confidence is less likely to stick in the memory. We need not be performing monkeys, but stressing key words explicitly and using discourse markers with clear emphasis and a tone that conveys enthusiasm will help engage students so they may then listen with intent. We must have undivided attention if students are to process complex new knowledge, therefore our tone must also convey authority. We may have physical positions of authority in the room where students expect you to speak from; we may move about the room to ensure students are actively listening, which requires often a clear and no-nonsense approach. A simple and obvious truth is that a great explanation is worthless if students are not listening to it!

9. Check understanding with targeted questions: One way to secure attention and to make any crucial modifications to our explanations is to ask targeted questions. By having a ‘no hands up’ approach on selected occasions can secure a higher degree of attention. By habitually getting students to comment on what one another has said can better keep all students listening actively (I prefer the ‘ABC Feedback model‘: Agree with; Build upon; Challenge). Questions can close in on the core message, but also open up to interesting analogies and ideas that deepen understanding. When considering an effective explanation a teacher should automatically have questions embedded in that explanation and be ready to flexibly respond to the answers, recasting and redirecting, even repeating the explanation if required.

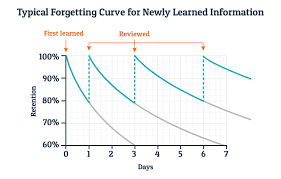

10. …and repeat: Knowledge stored in the long term memory is most typically information that is revisited, therefore a great explanation must be followed up if we are to maximise its value. The ‘Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve‘ is a nice visual way to remind us that we must give effective explanations, but then revisit the core message with spaced repetition, otherwise there is danger that it will be forgotten:

Great explanations are a foundation stone upon which great teaching is based. There is a complex interplay between our explanations, asking questions and eliciting feedback that if we master we will teach successfully. We should reflect and spend less time on jobs that are extraneous to the core of great teaching, such as creating limited use resources, or focusing upon the tools students use in our planning and get back to the our core practice of explaining, asking questions and giving feedback.

My core message: clear and effective explanations matter!

Further reading:

– Daniel Willingham’s book ‘Why Don’t Students Like School?‘ is an outstanding book that grounds effective explanations in scientific evidence.

– Dan and Chip Heath’s book ‘Made To Stick: Why some ideas take hold and other come unstuck’ presents a really helpful bank of examples and a easy method to make your messages memorable.

– Tom Sherrington’s blog post on ‘explanations‘ crosses very similar aspects to my post in with great success (read his brilliant series), complete with great images and examples.

Comments