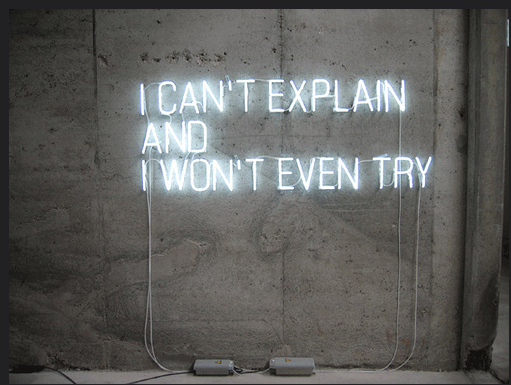

(Image via Stowe Boyd from Flickr)

“The human mind is an overconfidence machine.”

David Brooks, The Social Animal

Overconfidence is dangerous. How many ill-judged wars, invasions, crashes, economic downturns and worse, have been initiated by confident fools? Now, such overconfidence provokes such massive global catastrophes, but it also triggers trivial daily problems for us all.

We are all overconfident [yes – you too!] and it is somewhat necessary to help us get out of bed each day, so that we are not crippled by self-doubt and indecision. Still, we can better control our overconfidence in ourselves and in our students.

This handy British Psychological Society article provides us with a simple intervention to help prick the bubble of overconfidence. It really is easy: simply asking someone to explain how well we really know an seemingly familiar everyday objects, like printers and vacuum cleaners [you may wish to substitute some familiar processes from your teaching, like photosynthesis or subordinate clauses], in a thorough and clear manner.

So far, so familiar – teachers do this everyday don’t they?

Research by Washington and Lee University has shown that we don’t even have to demand a full explanation. They show that merely reflecting – “Carefully reflect on your ability to explain to an expert, in a step-by-step, causally-connected manner, with no gaps in your story how the object works” – on our explanatory ability helps to reduce estimates of our knowledge. In short, when we take a moment to consider what we don’t know it helps puncture overconfidence.

In my book for teachers, entitled ‘The Confident Teacher‘, I explore other methods to help us check our own overconfidence and that of our students (like finding a ‘critical friend’ and recognising our biases) , but using this strategy of ‘reflecting on explanatory ability‘ is a quick and easy strategy for teachers to effectively probe the true knowledge and understanding of our students.

Try it yourself:

Carefully reflect on your ability to explain to an expert, in a step-by-step, causally-connected manner, with no gaps in your story, how children learn.

Go on, give it a go.

The Curse of the Expert

It really isn’t as easy as we first think – even despite our expertise as an educator. In fact, we can sometimes suffer from the ‘curse of the expert‘ – that is to say, we are so experienced that we can make assumptions about what our novice students know, or forget some of the seemingly obvious steps that to us are long-since second nature.

We may also find it hard to explain exactly how and why we are so expert. Ken Koedinger, a professor of human-computer interaction and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University, argues that experts can articulate about 30 percent of what they know.

So, we are an overconfidence machine. This proves useful for us, but it can also prove damaging. Checking our overconfidence with a simple attempt at an explanation can help us.

You can find out much more about our confidence, including how to manage overconfidence in my new book: ‘The Confident Teacher‘.

Related reading:

The always excellent Annie Murphy Paul has written here about four secrets to lift the ‘curse of the expert’ – which is tantamount to our overconfidence in what we know based on our experience as teachers – ‘Four Secrets to Lift the Curse of the Expert‘

The peerless behavioral psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, has written here on the hazards of overconfidence: ‘Don’t Blink! The Hazards of Overconfidence‘

Comments