When I started teaching nearly two decades ago, I was a teacher of reading, writing, vocabulary, academic talk, and more. The problem was that I could do reading and writing, but I had little idea how to systematically teach the development of these vital skills.

Yes – I could model some writing and offer some handy stimulus material. I could also read through a Shakespeare play, with an interesting activity or two, but I had little idea how to teach a boy or girl who struggled to decode words, spell or write in sentences accurately, or who had significant comprehension gaps.

How many small losses were suffered because I didn’t know enough about literacy? And so, what do I wish I had known about literacy all along?

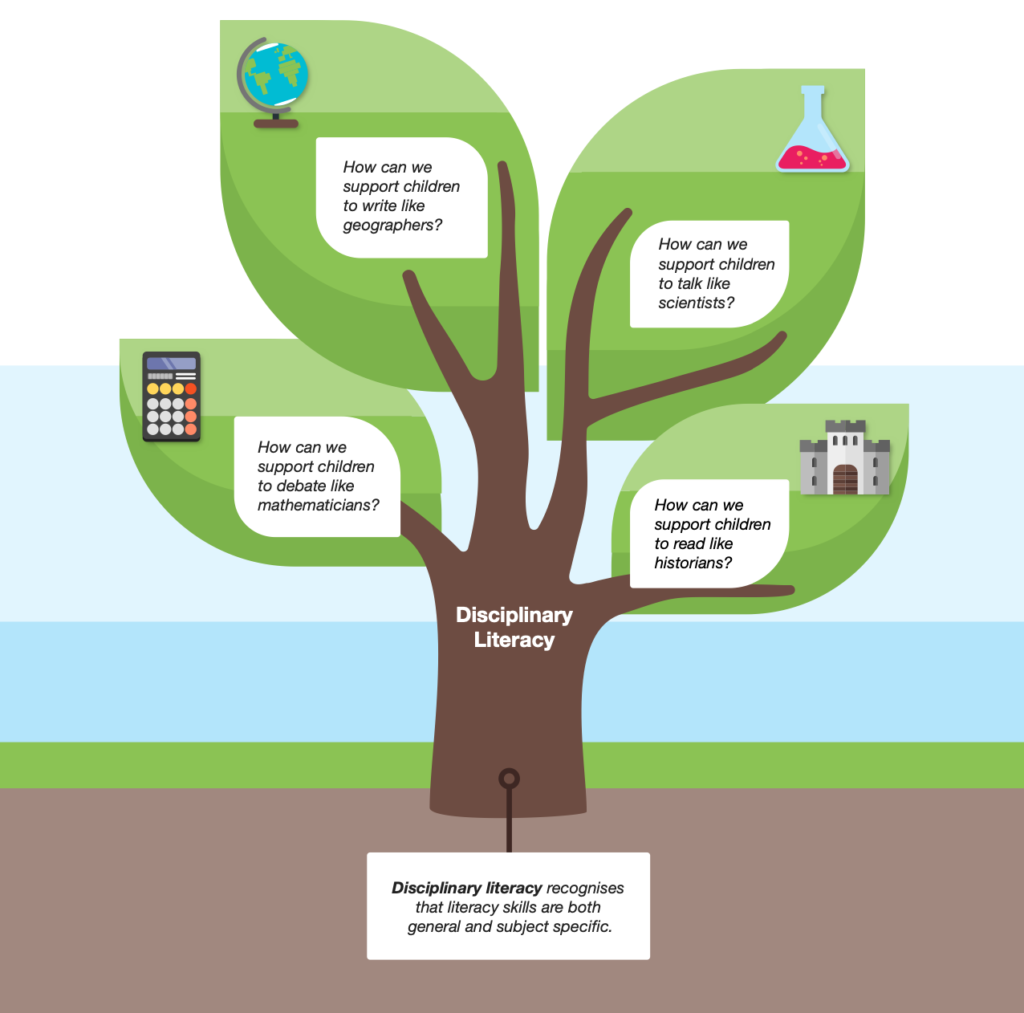

1. As pupils mature, they have to master the specialised ‘disciplinary literacy’ practices required in each subject domain

As children progress through primary school and into secondary school, the academic language that mediates the curriculum gets more complex and more subject specific. And so, literacy practices need to be responsive to the unique differences, such as how you read in history, or to write in science. The EEF guidance on ‘Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools’ exemplifies it thus:

“By anchoring literacy clearly in subjects, disciplinary literacy aims to support students to develop relevant ‘disciplinary habits of mind’. These are subtle but important differences in reading in subject specific ways. For example, in Biology, a student may read an informational text about photosynthesis and assume that is it an authoritative account, suppressing thoughts about the author of the text. In contrast, in the English classroom, a student could read with an active awareness of the author and the context in which the text was authored.”

Alas, too much of my training was a generic approach to literacy. A cluster of approaches to teach spelling, in relative isolation, simply didn’t prove nuanced and detailed enough to be embedded into my practice. A balance of understanding general literacy and disciplinary differences is required. We need explore the case for ‘disciplinary literacy’, before working as communities with subject expertise, so that we can best mediate the curriculum.

2. You cannot expect tools like a dictionary and a thesaurus to do the complex work of explicit vocabulary teaching

I always aimed to ensure a box of dictionaries and thesauri were available to my pupils. However, I didn’t always think to train them in their use. Using a dictionary is harder than you think:

“Learning from a dictionary requires considerable sophistication. Interrupting your reading to find an unfamiliar word in an alphabetical list, all the while keeping the original context in mind so that you can compare it with the alternative senses given in the dictionary, then selecting the sense that is most appropriate in the original context—that is a high-level cognitive task. It should not be surprising that children are not good at it.” (Miller and Gildea, 1987)

Miller and Gildea also showed the thesaurus can prove just as tricky. Comic examples of misapplying synonyms abound in the classroom (‘the blue chair was usurped from the room’; ‘I was meticulous about falling off the cliff’). A clear solution is to develop and sustain high quality explicit vocabulary instruction and immersing pupils in a vocabulary rich environment.

3. Reading skill is a complex combination of knowledge and an array of strategies that requires sustained explicit instruction.

Being a skilled reading adult reader is not an adequate basis to teaching pupils to become skilled readers. It can seem like reading is the most natural thing in the world, but it would be more accurate to say that it is a dizzyingly brilliant act and as complex as rocket science:

“…Reading and language arts instruction must include deliberate, systematic, and explicit teaching of word recognition and must develop students’ subject-matter knowledge, vocabulary, sentence comprehension, and familiarity with the language in written texts. Each of these larger skill domains depends on the integrity of its subskills.” (Louisa Moats, 2020)

From early years practitioners to college lecturers, and everyone in between, teaching the act of reading is vital. Unfortunately, continuing debates about the science of reading – termed ‘the reading wars’ – have obscured the reality that we know a lot about the essentials of teaching a child to learn to read, before going on to ‘read to learn’.

Paying close attention to developing curriculum and carefully calibrating background knowledge has become more widely known, the foundational role of phonics, the precise teaching of reading comprehension strategies, reading fluency, along with vocabulary instruction, all need attention. It is tricky work, but it is essential in opening up the curriculum for all of our pupils.

4. Improving boys’ reading is not solved by getting them to read about football

Too often, the solution for male pupils who struggle to read is to simply offer them a book on a topic they seemingly like. It would be great if enhancing skill and motivation was so easy. It isn’t. Though your prior knowledge does matter to reading (we can often mistake liking for knowing), you cannot mediate the school curriculum through the personal interests of thirty different children, nor are ‘boys’ a homogenous group.

I loved football when I was fifteen. But I enjoyed reading poetry.

We need to smash through seeming gender differences when it comes to literacy. It may be that feminine or masculine traits influence reading motivation over the actual gender of pupils. Many ‘boys’ may be interested in Marcus Rashford (quite rightly), but if you cannot read his biography fluently and with ease, your motivation to read is understandably dimmed.

Teacher knowledge of the act of reading (and related barriers) will matter. Teacher knowledge of reading choices will matter too, but not singularly. Becoming a better reader is the key, not some quick fix. Reading achievement will drive confidence and motivation in reading.

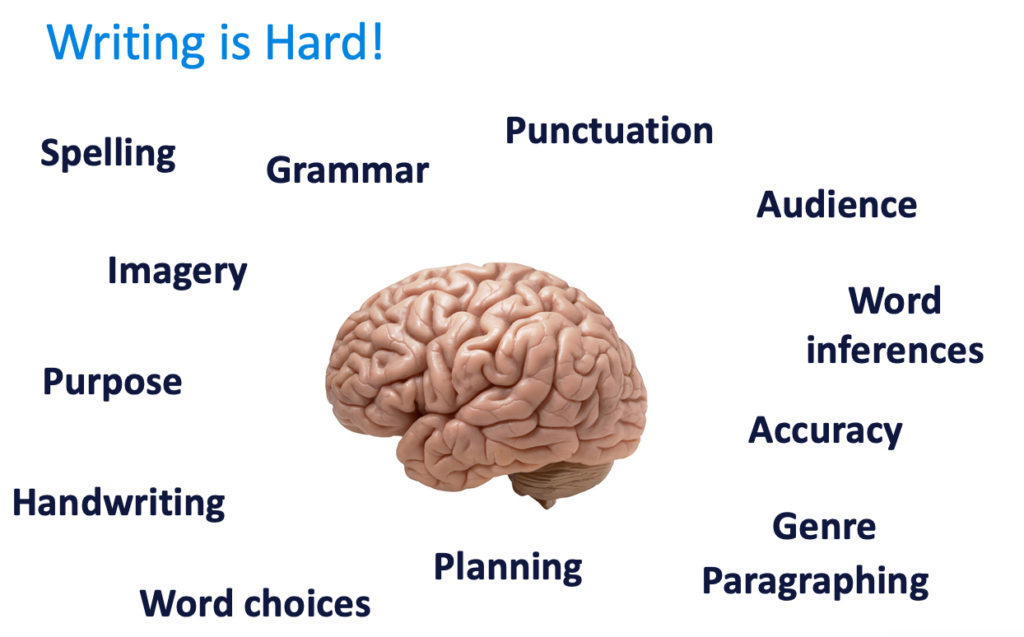

5. Writing is likely the most challenging cognitive act our pupils undertake in school

What is the other most complex act in the classroom that sits alongside reading? Writing.

Researchers have described it as sophisticated and demanding as playing chess. Indeed, making choices covering a vast array of ‘moves’ is indeed an apt description for the multi-faceted nature of writing.

It is an ingenious feat of knowledge and skill. As such, the writing process, so seemingly intuitive to skilled writers, needs to be broken down into small steps:

“Writing extended texts for publication is a major cognitive challenge, even for professionals who compose for a living. Serious writing is at once a thinking task, a language task, and a memory task. A professional writer can hold multiple representations in mind while adeptly juggling the basic processes of planning ideas, generating sentences, and reviewing how well the process is going.” (Ronald T. Kellogg, 2006)

Now, every teacher has a process for teaching writing – from sentences in GCSE science, to a story in English in year 4, but often teachers don’t share the same process. And so, weaker writers have their working memory overloaded.

Every teacher needs to understand the potential barriers thrown up by transcription (handwriting and spelling), before being deliberate about teaching complex sentences (such as using sentence combining strategies) and then the big game of extended writing.

Comments