‘Ro-man soc…i-e-ty… The army tried to con…q…u…er new lands for their v…ast Em-p-i…re.’

It is all-too common to hear arduous attempts at reading aloud in classrooms. Particularly with younger pupils, well-meaning enthusiasm, stretching their hands into the sky, is often followed by dysfluent reading. Teachers go on to select pupils to build their practice and help develop their reading fluency, but it is a process that is riddled with problems and challenges.

What do we need to do to get reading aloud – and reading fluency – right? Across key stages and subject domains, there are daily opportunities to improve pupils’ ability to read aloud more effectively.

What is reading fluency?

The word ‘fluency’ derives from Latin – ‘fluere’ meaning ‘to flow, stream or run’. This flow extended to water and rivers (‘flumen’ in Latin) but also to the privileged status of being a nimble and skilled speaker.

This flow of reading is all to familiar to teachers and anyone who has heard a skilled performer read aloud. Typically, our notion of reading fluency is rather tacit: something like how Stephen Fry reads those lovely audio books.

We can define it more precisely as follows:

“Fluent readers can read accurately, at an appropriate speed without great effort (automaticity), and with appropriate stress and intonation (prosody).”

EEF Guidance Report on ‘Improving Literacy at Key Stage 2’ (p19)

For many pupils, hearing the fluent reading of their teacher is a valuable necessity. When reading complex texts at the heart of the school curriculum, it will be the teacher who does the lion’s share of reading. They will offer that vital intonation – stressing key words and phrases – and infuse their reading with enthusiasm.

Listening to good reading fluency roles models is necessary but it is insufficient to see pupils develop their fluency. It is crucial that pupils themselves practise reading aloud.

Rather than pupils reading aloud at random – picking pupils because they have their hand up, or just to keep them focused – we should be more intentional about reading fluency practice and reading aloud.

Meaningful reading fluency practice (more than ‘no hands up’)

Picking pupils to read a class text at random, entitled ‘popcorn reading’ or ‘round robin reading’, has been challenged as flawed practice (read Professor Tim Shanahan on this topic HERE). The more lessons I observe, the more I recognise that reading fluency is best developed practising in small groups.

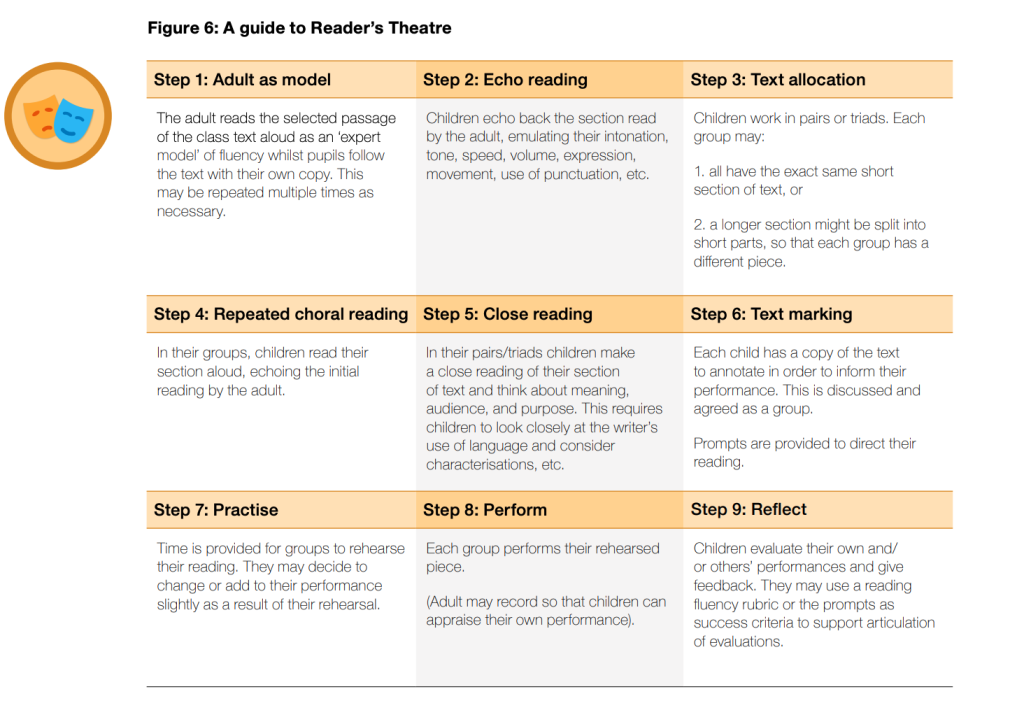

The research evidence indicates that ‘repeated reading’ is essential. This describes the practice of pupils re-reading a shorter practice a number of times to achieve a set degree of fluency. A sustained practice such as ‘Reader’s Theatre’ offers this important structure for purposeful repeated reading:

EEF – Improving Literacy at Key Stage 2: Reader’s Theatre

In KS3 classrooms, it may be that sustained repeated reading comes up against the barriers of limited curriculum time. If a sustained approach, such as ‘Reader’s Theatre’ or similar cannot be used, then we can turn back to teacher-led whole class approaches that can be woven into the fabric of lessons.

In MFL, maths or science classrooms, it can be normal for teachers to ask their pupils to repeat the pronunciation of key words or sentences to help consolidate their understanding. Teachers can deploy the following approaches to make small gains with reading fluency:

- ‘Choral reading’ – where everyone reads in unison. This can help reluctant readers, who can practise without being under the glare of their peers with ‘popcorn reading’.

- ‘Neurological impress method’ – where the teacher reads with a pupil as a pair, reading just ahead and slightly louder, thereby ‘impressing’ a confident reading of the word. [This can help struggling readers as a form of individual support]

- ‘Echo reading’ – where the teacher reads aloud, with a focus on listening for fluent reading before pupils then echo the passage. This can be helpful with a difficult passage where pupils benefit from listening to the words.

All of these approaches are manageable but meaningful examples of fluency practice. They can also be deployed if teachers are looking to work with a smaller group of pupils for targeted academic support, during activities like independent reading or similar.

We can choose pupils to read important passages from classroom texts, but some repeated reading in pairs (ideally with a focus on fluency in their peer feedback) can greatly enhance this practice. The more intentional we are about reading aloud in class, and developing fluency, the better.

Reading fluency is often described as the bridge to comprehension – given it helps consolidate word reading and can enhance comprehension. It offers a useful glimpse into the reading comprehension of a passage too. Put simply, the words or phrases pupils struggle to read aloud are typically (but not always) words they are struggling to comprehend.

There are diagnostic assessments available for reading fluency, such as DIBELs (which comes with a wealth of useful resources), or the ‘Multi-dimensional fluency rubric’ developed by Zutell and Rasinski. In addition, many schools are utilising technology to focus on reading fluency. For instance, Microsoft have developed ‘Reading Progress’ on their Teams platform.

Reading fluency is no quick fix to cure all reading development issues, but it is a manageable way to enhance pupils’ reading and enhance the comprehension of the texts we choose to read in the curriculum.

Related Reading:

The EEF have collaborated with Herts 4 Learning on the following resources:

- Reading fluency misconceptions – HERE.

- What might fluency look like in the classroom – HERE.

- Reading fluency glossary – HERE.

[Image: ‘Reading’ by David Ross]

Comments