I have written a countless number of essays. At school, university, and back at school again, showing my students how to do it. In my fourteen years teaching I must have modelled hundreds of essays. I have likely set and assessed thousands of the blighters.

My go-to strategy has always been to model the essay writing process, to make visible how an expert essay writer thinks. Students are often left baffled by how fast I can make decisions about my essay, how I can pluck sophisticated academic words seemingly from the ether, and then write with speed as well. With sore hands and muffled complaints, students have been pulled along on the path from novice to expert.

In my recent thinking on assessment – see my blog on ‘The Problem with Past Papers‘ for more – I have looked to go further and to seek out deploying more effective diagnostic assessments to help my students develop their essay writing skill.

I gave the example in my last blog of setting ‘An Inspector Calls‘ essay to my year 10 class, in preparation for them doing a summative essay writing task. [Dear reader, those essays sit in my work bag right now, taunting me] I described how my students had so many errors and gaps in their knowledge with their last essay, that it made my feedback scattergun and not as effective as it could be.

I went onto write the following about the complexity of essay writing:

“They had to play the ‘big game’ of remembering quotes, writing insights about character, theme, social context, all in a coherent argument structure, with written accuracy, without the practice and focus on knowledge to do all of these things fluently.”

In truth, writing a good essay takes a host of knowledge and expertise. For English Literature then, we need to distill down that complexity into more manageable diagnostic assessments, so that our students can gradually develop from their novice status towards something like expertise. To use an analogy, writing a great essay is like the creation of a strong rope, with each sub-strand being woven together in unison. Each strand of the rope can represent the crucial knowledge required for essay writing success.

If we are to teach great essays, then we need to define the strands that will be woven together to form the rope. For my GCSE students, you can refer to the exam board rubrics, but they too often prove vague and not as definitive as we would like. My judgment is that the key strands of the great essay writing ‘rope’ comes down to students knowing (declarative knowledge) and doing (summative knowledge) the following:

- Display knowledge and understanding of how the social context influences the writer and their text (including how different audiences may respond to the text);

- Display knowledge and understanding of the character, themes and language of the text, making connections and inferences from across the text;

- Display knowledge of the writer’s choice of literary devices and generic conventions, based on a wider knowledge of literary history;

- Select, retrieve and interpret evidence (predominantly in the form of quotations);

- Make inferences from that evidence on the writer’s vocabulary choices based upon a broad and deep academic vocabulary knowledge;

- Plan and organise an essay into a coherent argument, linking salient points that address the essay question;

- Write with accuracy and clarity, including the use of lead sentences, discourse markers and academic vocabulary, all deployed in an appropriate academic style (written in the passive voice, using nominalization etc.).

I think we can get lost down the rabbit hole discussing the meaning and difference between words like ‘evaluate‘ and ‘analyse‘. I have ignored exam rubrics for this reason. I am confident that if my students could address the above strands, practising each in isolation, before, over time, weaving them together into the ‘rope’ of a full, expert essay, that my students would write great essays for any English Literature qualification.

I think there is something useful about the order in which I have presented the strands above. By beginning with the ‘big picture‘ of the social and literary context, we give our students a schema – or a broader framework – in which to root their knowledge of the text. If the text is ‘Animal Farm‘, they need to see the big picture of Communism and Russian history (1), linked to the characters and themes (2), that are couched in a dystopian fairytale (3). Given that ‘big picture‘, they can begin to select evidence and make inferences and interpretations from the text.

Assessing Strand 1

Let’s take the first strand and consider how we can use diagnostic assessments to better develop their ability to ‘Display knowledge and understanding of how the social context influences the writer and their text (including how different audiences may respond to the text)‘, long before they are asked to do so in the ‘big game‘ of writing a full, timed essay.

I think the different strands lend themselves to different diagnostic assessments. Knowledge and understanding of social context lends itself to cumulative quizzing. If we take ‘Animal Farm‘ once more, then a regular quiz to consolidate which historical figures are represented by which characters in the novella. This is crucial ‘base knowledge’ and can be assessed rather simply. Once students have consolidated these basic facts, they can begin to display understanding of those characters: how they change; their relationships with other characters; the themes and ideas they relate to, and their symbolism etc.

Another apt assessment for strand 1 would be using graphic timelines, both for how the text fits in a broader literary tradition, as well as a timeline for the text itself (for example, with Animal Farm, the characters actions neatly translate to historical acts, such as the Russian revolution etc.)

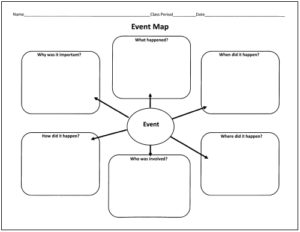

If we are looking to diagnose our students’ understanding of different audience responses to a text, another approach is using other types of graphic organisers, such as a Venn diagram, a ‘mind map’, or an ‘event map’ – see here:

We can begin to increase the degree of challenge, and the related complexity of the diagnostic assessment, by getting students to relate their knowledge of a contextual factor to themes in the text, as well as the audience’s interpretation of theme and context. Here ‘short answer questions‘, that require a paragraph length response, are more appropriate assessment tools. It is this progression of assessment that is important.

Still, we must hold our nerve that doing smaller, more precise diagnostic assessments better secures their knowledge and understanding than playing the ‘big game‘ of writing multiple essays. I haven’t even mentioned the potential reduction in teacher marking. [Ignores siren calls from the marking unceremonious neglected in my school bag]

Assessing Strand 4

Now, you may have noted that I missed out strands 2 and 3, but I wanted to address the use of evidence, particularly the use of quotations, given this is a real pressure point with the new GCSEs, due to the nature of the closed book examinations.

There has been much gnashing of teeth at the prospect of students memorising over 200 quotations for English Literature. It certainly will separate out children who are trained to remember quotations effectively and cumulatively, over those who are not, but given the challenge, we should deploy good diagnostic assessments that not only help us grasp our students’ current progress, but actually help them reinforce their memory and understanding of quotations.

As indicated in the wording of strand 4, ‘select, retrieve and interpret evidence (predominantly in the form of quotations)‘, we can more effectively separate out what we want our students to know and can do with evidence from the text.

We often miss out the ability to ‘select‘ quotations as a first step. We need to train our students to pick the ‘right’ quotes. With tongue in cheek, I often describe the right quotes to learn as ‘Swiss-Army-Quotes‘. That is to say, those quotations that you can use for a multitude of essay questions, as they encompass many different ideas, themes or issues from the given text. An effective essay writer can only store so many quotations, so they need to be pertinent and selected judiciously.

In terms of diagnostic assessments for selecting good quotations, we can start with using multiple choice questions that get students to correctly relate quotations to individual characters or themes. We can get students to rank order quotations with regard to their relevance, relative importance etc. We can get them to select quotations when given a specific character, theme or prospective essay question.

If we want to test and learn how well our students ‘retrieve‘ quotations then we can set them timed challenges – with a ‘Quotation Quest‘ (a challenge to collate key quotes for whatever purposes that you identify) which proves great for competition; or we can quiz them on what chapter/stave/stanza/page quotations are from. Alternatively, or concurrently, we can get students to devise a quotation timeline, that sorts quotations by chronological order, and more.

With each of the ‘select‘ and ‘retrieve‘ diagnostic assessments, we can, if we choose to, record their relative progress. It is relevant, over time, we can increase the degree of challenge for these tasks by factoring in timed conditions.

When it comes to ‘interpret‘, we need different, more nuanced diagnostic assessments. Short answers quizzes can get students to respond to individual quotations. We can assess their understanding in such quizzes. We can assess them orally, with a ‘Just a Minute‘ activity, whereat they have to say as much as they can about a given quotation. Of course, targeted questioning can elicit how well they can interpret a quotation. I like the idea, rather than tackling essays, or PEE paragraphs (PEAL, PETAL, whatever you call it!), of doing what Katie Ashford labels ‘show sentences‘ (see here for more: ‘Beyond the Show Sentence‘): effectively a concise response to a given quote.

Of course, after we have honed and assessed this more precise textual knowledge, we can more consistently combine ‘select‘, ‘retrieve‘ and ‘interpret‘ procedural knowledge in singular tasks. Over time, we can be more assured they are ready to write a great essay. What we need to do is use diagnostic assessment – testing as learning – to ensure that students can automatically select the ‘right’ quotes, retrieve them quickly, before interpreting them skillfully.

Tying it all together

I know English teachers have enough to do, but if we are devote our time, it shouldn’t be wading through endless mock exams; it should be developing our subject knowledge – particularly our text specific insights – and developing and sharing better diagnostic assessments for the texts that we teach.

It may mean that we have to reconsider our typical teacher habits and go back to the drawing board with assessment of texts. If we get our assessment of learning right, we will likely be marking fewer, but better essays. After spending countless hours marking a few thousand, I’m ready for better essays!

Read PART TWO – the follow up outlining the seven strands.

There is obviously work to do with regard to the assessment strands that I have outlined above and the attendant range of diagnostic assessments. If you have any insights, criticisms or ideas, please do share. I aim to follow up this blog with a completed set of essay writing strands, with ideas for apt diagnostic assessments, but I would welcome input, suggested changes, and any additional ideas before I do that.

Cover image via PhotoSteve101: https://www.flickr.com/photos/42931449@N07/5418402840

Comments