Thinking about better assessment is not always at the forefront of the mind of a busy English teacher. We are so hassled by marking, planning and well, teaching lots, that we keep our nose to the marking grindstone and, well…just keep on going.

More recently, I have been trying to consider how to improve as a teacher and, inevitably, it got me thinking about assessment. After marking thousands of essays, I wanted to ensure that I was asking students to undertake the best formative assessment and so that my precious time given over to my feedback efforts were worthwhile.

With this in mind, I put aside the dubious language of exam board AOs and considered what makes a great essay. I came down to the following strands, woven together into the metaphorical rope of a complete essay:

- Display knowledge and understanding of how the social context influences the writer and their text (including how different audiences may respond to the text);

- Display knowledge and understanding of the character, themes and language of the text, making connections and inferences from across the text;

- Display knowledge of the writer’s choice of literary devices and generic conventions, based on a wider knowledge of literary history;

- Select, retrieve and interpret evidence (predominantly in the form of quotations);

- Make inferences from that evidence on the writer’s vocabulary choices based upon a broad and deep academic vocabulary knowledge;

- Plan and organise an essay into a coherent argument, linking salient points that address the essay question;

- Write with accuracy and clarity, including the use of lead sentences, discourse markers and academic vocabulary, all deployed in an appropriate academic style (written in the passive voice, using nominalization etc.).

I considered the following approaches to creating diagnostic assessments for each strand. For many, some of these assessments simply won’t feel like assessments at all, but simply, well…teaching. It is symptomatic of how far summative assessment is ingrained in our thinking that we consider final assessments, like mock examination essays, as the dominant way to train students . Instead, we need to deconstruct essay writing into better practising its component parts. The following ideas offer suggestions to do just that:

Assessing Strand 1

Knowledge and understanding of social context lends itself to cumulative quizzing. If we take ‘Animal Farm’ by example, then a regular quiz can help consolidate which historical figures are represented by which characters in the novella. This is crucial ‘base knowledge‘ and can be assessed rather simply. Once students have consolidated these basic facts, they can begin to display understanding of those characters: how they change; their relationships with other characters; the themes and ideas they relate to, and their potential symbolism etc.

Another apt assessment for strand 1 would be using graphic timelines, both for how the text fits in a broader literary tradition, as well as a chronological timeline for the text itself (for example, with Animal Farm, the characters actions neatly translate to historical acts, such as the Russian revolution etc.)

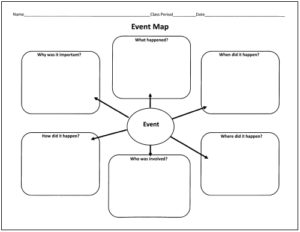

If we are looking to diagnose our students’ understanding of different audience responses to a text, another approach is using other types of graphic organisers, such as a Venn diagram, a ‘mind map‘, or an ‘event map‘ – see here:

We can begin to increase the degree of challenge, and the related complexity of the diagnostic assessment, by getting students to relate their knowledge of contextual factors to themes in the text, as well as the audience interpretation of theme and context. Here ‘short answer questions‘ that require a paragraph length response are more appropriate assessment tools. It is this progression of assessment that is important. Also, an organised discussion, organised around principles of ‘Socratic circles‘, or a debate, either with more formal rules, or orchestrated more loosely, can capture knowledge and understanding of audience attitudes successfully.

Assessing Strand 2

The diagnostic assessments that best attend ‘character‘, ‘themes‘ and ‘language‘ of the text will prove subtly different. To best develop a knowledge of character and theme, cumulative quizzing to consolidate core knowledge and to diagnose their gaps, is once more an integral assessment opportunity. Short answer questions can also tease out core knowledge.

Once more, graphic organizers appeal to assessing ‘character’ and ‘theme’, as they encourage students to organise their ideas and make connections across ‘characters’ and ‘themes’ from the text. A simple ‘diamond 9‘ approach can get students to consider ‘character’ and/or ‘theme’ hierarchies:

A ‘concept map‘ is a good way to provide an diagnostic assessment for students to make connections, organising their knowledge around a key ‘theme’. The focus on hierarchy in a concept map lends itself to address the power of characters, or the relative importance of themes.

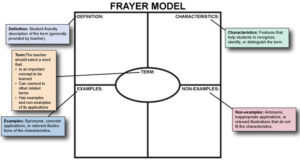

Exhibiting a close analysis of language is so crucial knowledge for every student. The depth of analysis in many an essay is defined by how many nuanced inferences students can make about individual word choices (including idioms and metaphorical language). The ‘Frayer Model‘ is a good way to glean understanding from individual language choices:

Cloze exercises have a value in getting students to choose between appropriate words to describe aspects of the text, or to generate their own answers. ‘Choose the closest definition‘ is a variant of multiple choice questions, simply offering potential definitions for key language choices, proving particularly useful when students have shaky knowledge and understanding.

Assessing Strand 3

When it comes to assessing language, then we first need to ensure that students understand the basic definition of a term. Many an English teacher has re-explained the difference between a simile and a metaphor…over and over! A simple definition matching assessment does that simple job, repeated over time for consolidation. Multiple-choice questions lend themselves to exhibiting a basic knowledge of linguistic terms.

Of course, feature spotting can prove a limiting factor for students; they need to be able to describe the effects creating by linguistic devices and generic features. Getting students to provide multiple examples of linguistic devices, with a simple ‘explain > exemplify‘ diagnostic assessment, sees them explain the linguistic device and its typical effect, before then exemplifying it with two or three of their own examples.

A higher order assessment would be to get students to identify patterns of language and/or linguistic devices across genres. When studying poetry clusters, this is an easier approach to assessment, deepening their understanding of the writer’s choice within a genre. Concept maps lend themselves well to analysing a genre, or comparing poems within a cluster, whereas more extended oral presentations can help determine how well students’ exhibit knowledge of genre and writers’ linguistic methods in greater depth.

Whenever students are faced with a graphic diagnostic assessment, like a concept map, we can always broaden the assessment, garnering more knowledge about the student’s understanding, by combining the concept map with an expectation that they elaborate with an oral presentation for X minutes.

Assessing Strand 4

As indicated in the wording of strand 4, ‘select, retrieve and interpret evidence (predominantly in the form of quotations)‘, we can more effectively separate out what we want our students to know and what they can do with evidence from the text.

We often miss out the ability to ‘select‘ quotations as a first step. We need to train our students to pick the ‘right’ quotes. With tongue in cheek, I often describe the right quotes to learn as ‘Swiss-Army-Quotes‘. That is to say, those quotations that you can use for a multitude of essay questions, as they encompass many different ideas, themes or issues from the given text. An effective essay writer can only store so many quotations, so they need to be pertinent and selected judiciously.

In terms of diagnostic assessments for selecting good quotations, we can start with using multiple choice questions that get students to correctly relate quotations to individual characters or themes. We can get students to rank order quotations with regard to their relevance, relative importance etc. We can get them to select quotations when given a specific character, theme or prospective essay question.

If we want to test and learn how well our students ‘retrieve’ quotations then we can set them timed challenges – with a ‘Quotation Quest‘ (a challenge to collate key quotes for whatever purposes that you identify) that can prove great for some competition; or we can quiz them on what chapter/stave/stanza/page quotations are from. Alternatively, or concurrently, we can get students to devise a quotation timeline, that sorts quotations by chronological order, and more.

With each of the ‘select‘ and ‘retrieve‘ diagnostic assessments, we can, if we choose to, record their relative progress. It is relevant, over time, we can increase the degree of challenge for these tasks by factoring in timed conditions.

When it comes to ‘interpret‘, we need different, more nuanced diagnostic assessments. Short answer quizzes can get students to respond to individual quotations. We can assess their understanding in such quizzes. We can assess them orally, with a ‘Just a Minute‘ activity, whereat they have to say as much as they can about a given quotation. Of course, targeted questioning can elicit how well they can interpret a quotation. I like the idea, rather than tackling essays, or PEE paragraphs (PEAL, PETAL, whatever you call it!), of doing what Katie Ashford labels ‘show sentences‘ (see here for more: ‘Beyond the Show Sentence’): effectively a concise response to a given quote.

Assessment Strand 5

‘Making inferences‘ from ‘writer’s vocabulary choices‘ is quite simply integral to literary analysis. Many of the assessment opportunities already described in the previous strands effective diagnose students’ knowledge and understanding for this strand too. From targeted questioning and structured discussion of relevant evidence, ‘Just a Minute‘ presentations, multiple-choice questions to tease out difference inferences, ‘show sentences‘, model paragraphs, and more. The ‘Frayer Model’, though appearing simplistic, can encourage really deep word knowledge, isolating the choices of the writer with real precision, which is so integral to good analysis of language.

You can reverse engineer some of the above for variety. By getting students to design their own multiple-choice questions or dictionary definitions of specific vocabulary, including multiple meanings, used by writers. They can also devise flashcards, based on writer’s vocabulary choices, that both exhibit their knowledge and understand, whilst creating a useful tool for future learning.

Assessment Strand 6

Planning to ‘organise an essay into a coherent argument‘ is a relatively straight-forward strand of procedural knowledge to develop and to assess. We can get students simply devising skeleton essay plans for given questions, to giving extended oral presentations on a given essay question or point of debate.

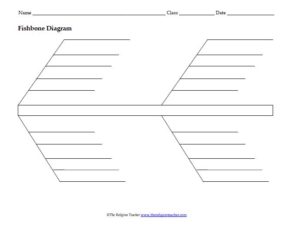

We can use paragraph sort activities, whereat students have to organise paragraphs into a coherent argument and justify their response. Graphic organisers that convey essay structures can work effectively, like a fishbone diagram graphic organiser:

Assessment Strand 7

Writing with accuracy and clarity under the pressure of timed constraints is very different to writing and drafting, making edits and improvements. Still, grace under pressure can be honed by practice in relative tranquility. Deliberate practice with teacher feedback here often comes down to diagnosing an issue, such as a weak control of syntax, or an absence of discourse markers. We can work backwards from common issues within our groups by then setting short tests and practice on isolated aspects of writing until they are corrected and become automatic.

Once more, distilling down the complexity of a full paragraph can come down to crafting and drafting a perfect sentence. Once more ‘show sentences‘ are useful. From crafting the perfect sentence, students graduate to the ideal paragraph, before then practising connecting lead sentences…you get the idea!

Writing with an academic voice can be trained in various ways, from translation exercises that see students translate a flawed, informal essay paragraph into one that adheres to an apt academic style, to being explicit about an academic writing voice by expecting such phrasing and use of discourse features in their verbal interactions. Once more oral assessments can be utilised as a diagnostic assessment, such as through a formal debate, of course, priming students to write their argument having rehearsed in debate.

You can read look back on PART ONE of the series for more.

Comments