Every teacher can share ample examples of their students struggling to learn independently. From giving up during an extended piece of writing, to getting stuck and stopping with tricky algebra problems, or forgetting homework and avoiding revision.

A lack of independence is a commonplace issue in education, but less common is an agreed way forward to best address the issue of inadequate independent learning or ‘learned helplessness’.

One issue is that every teacher can have a different idea about independent learning, how to develop it, and what it should look like in their phase or subject. If we can better define the concept – as well as developing a clear mental for model for why it typically goes wrong and fails – we make a key first step to achieving teaching and learning success.

From ‘learned helplessness’ to ‘learned industriousness’

A phase I particularly like, that adds specificity to the concept of independent learning, is what Barbara Oakley described as ‘learned industriousness’. Why do I particularly like this phrase? For one, it challenges the misconception about the innateness of effective independent learning. Even for the pupils who appear most helpless, a sustained approach to teaching strategies to develop independence is workable. With high quality teaching, it can be learned by anyone.

Why are some pupils more seemingly inclined to ‘learned industriousness’? The answers are unsurprising. Teaching, modelling, and practice are key. For pupils who have ‘learned industriousness’ modelled and reinforced outside of the classroom environment, there are likely to be clear gains for classroom tasks over time.

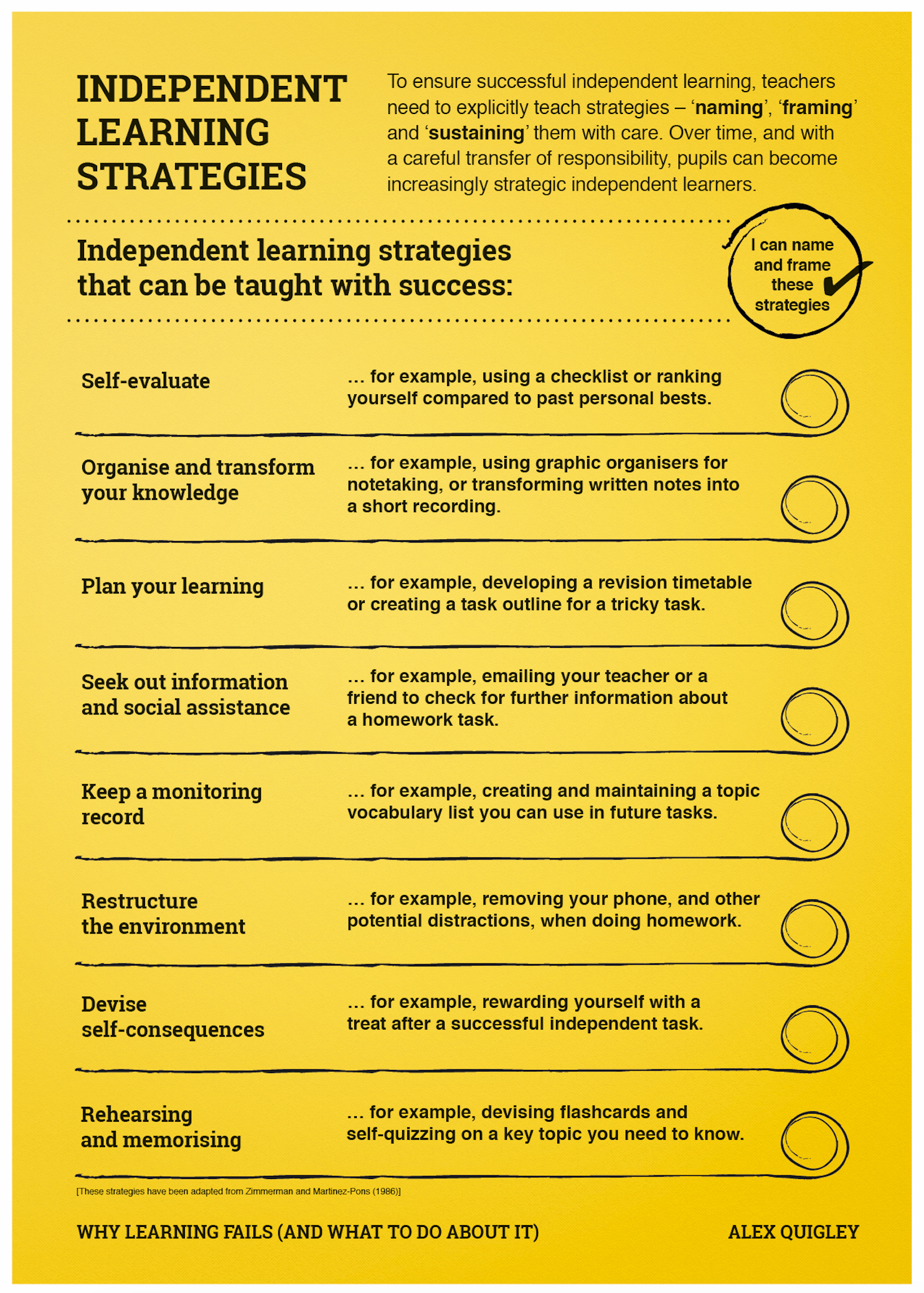

In my new book, ‘Why Learning Fails (And What To Do About It)’, I explore pupils inability to consistently undertake independent learning strategies. A related resource – see below – shares some of the strategies outlined in the book:

‘Independent Learning Strategies’

A list of strategy is no quick-fix to what are complex challenges of course. Many of these approaches have been shared with best intent, but little has changed. For me, it is crucial that we name such strategies, and then 'frame' them with clear action-steps and subject and phases examples. Too often, pupils try them once, don't quite understand how to enact them well, so drop the strategy and carry on regardless.

Naming, framing and sustaining

The key issue of mastery of such strategies to the (hard-won) point where they are a habit. The 'sustaining' phase of such strategy instruction is key. What does this transfer of responsibility from teaching the strategy to independent application include? Again, unsurprisingly, repetition matters - but, crucially, without sustained feedback and practice of varying the approach in different contexts, it might not stick as a strategy.

For example, using graphic organisers to 'organise and transform your knowledge' includes lots of choices between different models of organiser (Fishbone diagrams for cause>effect; Venn diagrams for comparison etc), when to use them, for how long, and more. Pupils need worked examples, including some variation of style and use, so that pupils start to recognise the underlying features of the organiser.

'Naming', carefully 'framing', and planning for 'sustaining' the use of these independently learning strategies is a strong start. It rejects the notion that learned helplessness is an acceptable expectation for any pupil and it promotes learned industriousness in concrete and specific fashion.

If you are interested in learning more about improving independent learning, you can grab a copy of my book. To access free resources – including the high-res copy of the ‘Independent Learning Strategies’ resource – simply sign up to my new website.

Sign up to my blog for new FREE resources on 'Why Learning Fails'.

Order from Amazon now HERE

Order from Routledge now HERE.

Comments