Is ‘instructional coaching’ the next big thing?

Maybe I should be a little clearer: by ‘next big thing’, I wonder whether a nation-wide wave of enthusiasm for this particular professional development vehicle will soon wane, and the promise of coaching will quietly fold into mass of unshared failures in schools.

In their book, ‘The Next Big Thing in School Improvement’, Professor Becky Allen, Ben White, and Matthew Evans, present a harsh reality that many well-meaning movements in education come in waves, but that the complexities of the school system means that those waves quickly and inexorably crash and wash away on the shoreline. There is too-little time to learn from our mistakes, nor evaluate and share our errors, so we beat on and ride the next wave.

Given the quick scale-up of instructional coaching in England – wedded to a host of different programmes and practices – it is a likely candidate for the current ‘school improvement wave’.

The promise of instructional coaching

The promise of instructional coaching is writ in a range of research evidence. US evidence reviews on coaching show a range of broadly positive studies. Too few aspects of educational research evidence offer us a ‘good bet’, so we should give it an enthusiastic look.

This undoubted positivity attached to coaching is often wedded to how it can position professional dialogue at the heart of school improvement. The outmoded model of five INSET days full of random ‘train and pray’ sessions appears impersonal and ineffective by comparison.

Not only that, in national programmes for new teachers, coaching is integrated as a natural-seeming model for supporting new teachers. If a positive school culture can influence school, and teacher improvement, then maybe coaching can be that all important vehicle for improvement?

Coaching resources and tools are being shared liberally – along with platforms, structures and tools to support this coaching model – so enthusiasm may translate to sustained success.

What are the potential problems?

What exactly do we mean by ‘instructional coaching’ anyway?

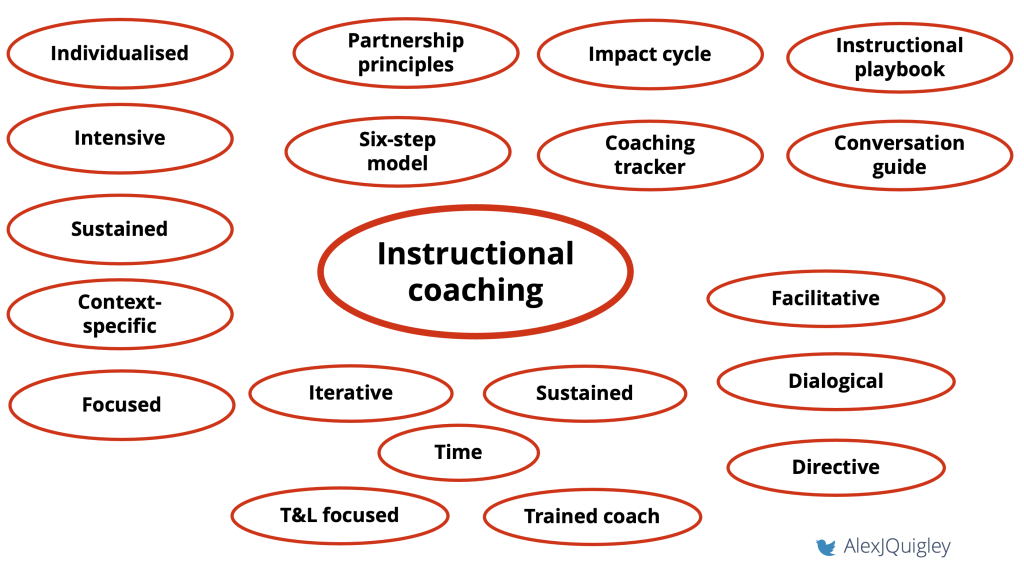

At the recent researchED Warrington conference, I shared a host of the key words, search terms, along with the catchy phrases that attend this popular mode of coaching.

We can make obvious claims for the essential principles needed for effective coaching. It needs time and resource. Some researchers argue it needs to be individualised, sustained, intensive, and focused. But what exactly do these words mean? They sound like well-meaning principles, but can we precisely define them, observe them, and evaluate their success?

Depending on who you ask, instructional coaching could be ‘facilitative’, ‘dialogical’, or ‘directive’, or a bit of a mix depending. If you read your Jim Knight, you may be familiar with ‘Impact cycles’ and ‘Instructional playbooks’, but if you prefer your instructional coaching with a ‘Leverage Leadership’ flavour, you may be deploying the ‘Six-step model’ or the ‘conversation guide’ for your ‘steps’ approach.

In short, there is a lot of language describing coaching. There are, of course, lots of different types of coaching that isn’t ‘instructional coaching’, with yet more language to muddle. And there is undoubtedly a lot of potential for confusion and miscommunication.

We could be doing instructional coaching, but it is nothing like the school down the road. And who really knows if it is working anyway?

Then we get onto the topic of time. We already see that mentors don’t have enough time with early career teachers. Why would coaching mobilised across entire schools fare any better? There is no reason to believe that a new fast lane of extra time is being offered to leaders and teachers to get this right.

Often, we spend so much time getting the vehicle of instructional coaching moving that we don’t get underneath the crucial ‘what’ of what is being coached. Much of the evidence we cite from the US is rooted in literacy instructional coaching, but in England there is seemingly less of a focus on the ‘what’ for the current coaching wave (although there are popular teaching and learning programmes that are being wedded to coaching that show promise).

Coaching is tricky. It relies on a school culture; expertise; time; efficient support structures; flexible systems… and so on. In short, there are a lot of support factors needed, and lots of ways for it to go wrong!

Put simply, a school improvement wave is most likely to break when it crashes into the complexity of real school life.

Should we chuck out instructional coaching?

Instructional coaching needn’t be dismissed as a fashion or fad, like growth mindset, was harshly treated before it, but we should face up to the high likelihood of failure (like most things in school improvement).

The failure to scale up instructional coaching in well-funded programmes in the US should give us pause. We can ask purposeful questions that can mitigate failure and sustain the wave into a stable tide of improvement:

- Does everyone involved have a shared language to coaching for improvement?

- Do coaches and coachees have the requisite time to build their knowledge, practice techniques, and embed changes?

- Are instructional coaching processes supported by a positive school culture (and what exactly does that mean)?

- Are coaches and coachees supported with a focus on the ‘what’ of curriculum, pedagogy, along with knowledge of pupils and their learning?

- Does our coaching include a balanced range of professional development mechanisms (see the EEF review and guidance report on ‘Effective Professional Development’)?

Comments