This short blog series is targeted at literacy leaders – either Literacy Coordinators, Reading Leads, or Curriculum Deputies – with a key role in leading literacy to ensure that pupils access the curriculum and succeed in meeting the academic demands of school.

Few school leaders get trained in communications. Yet, in almost all facets of school leadership, savvy communication is necessary. From sensitively worded emails to colleagues, school website page updates, job adverts, to the many communications with parents. When you are tasked with leading an area like literacy, you are forced to consider an array of tricky communication choices to elicit support for successful change.

It is helpful to consider leading literacy like a successful political campaign. You need a compelling strategy, clear messaging about any changes, and a solid story to convince busy teachers to buy into your plans. Easy, eh?

We can distil such communications into principles to navigating communicating complexity well.

5 Principles of communicating complexity

1. People follow people and their stories over policy documents. A literacy leader is often tasked to write purposeful policies about literacy practices, such as approaches to SPaG, whole school reading, and more. The problem is that teachers are too busy to read them anyway. Given that we privilege stories psychologically, we should work hard to identify a small number of concrete stories that convince teachers why a change is necessary, alongside characterising that change. Some of my most memorable professional development involved the video of struggling pupils from my school explaining what support strategies helped them most. It was people and their stories that instigated my habit changes – not the small print in a literacy policy.

2. Little and often is vital for busy teachers. There has been an entire industry built on behaviour insights and how to adapt your communications for a busy audience (see the BIT team and their excellent EAST Framework). We see it in education. Texts to parents approve to prove accessible for parents, so why wouldn’t the same principles of regular nudges work for teachers? Some of the most effective school approaches I have seen recently offer regular emails nudges, with positive reminders by slotting in good practice into weekly slots that work with the rhythm of the school week.

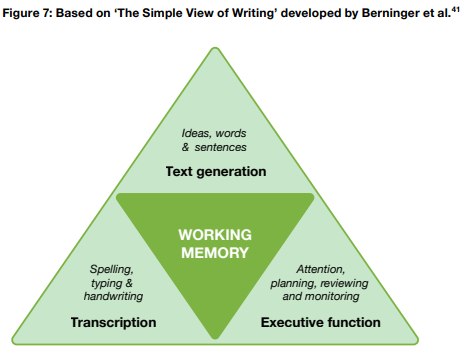

3. Short and sweet – like a text or a tweet. Not only are teachers busy, but their day is so chock-full of decison-making and an array of practices, that they understandably find it hard to translate complex insights into concrete actions. Helpfully, literacy does include accessible models, such as the ‘Simple View of Reading‘, the ‘Reading Comprehension House‘, the ‘Simple View of Writing‘ etc. By shrinking insights down to a working model, you then offer a hook upon which some practices can hang. For instance, with the ‘Simple View of Writing‘, you can more easily cluster practices to improve pupils’ writing. The next ‘short and sweet’ step has to be selecting a small number of actionable practices than can be implemented well (doing even few things well may just be at the edge of manageable for professionals with limited bandwidth).

4. Over-communicate, over-communicate, over-communicate. There is an adage that when you give a talk on a topic for the hundredth time – feeling the message is worn and tired – someone is hearing the message for the first time. Plan to communicate your literacy strategy… and bake in repeating that communication. For instance, communicating about how to develop whole class reading may get tuned out of deleted emails, not quite make the agenda in meetings, and be forgotten as it is relayed in the far reaches of a CPD twilight. Over-communicating your literacy messages, replaying that central story, can be done if you have distilled insights into those ‘short and sweet’ messages that are so vital for any working literacy strategy.

5. Pay attention to multiple audiences. It takes a village to raise a child; it takes a school community to enact a literacy strategy. It may be that approaches to reading or writing are communicated and practised with teachers, but if we are to clearly and concisely mediate similar messages to both pupils and parents, we can create a positive alignment. Sometimes it take a little reciprocal pressure, knowing everyone else knows about the literacy focus, for it to be sustained when everyone is tired, busy and reverting to old habits. Consider how to calibrate the message to different audiences with very different levels of expertise (remember to get the timing right for time-poor parents), but do consider over-communicating to all audiences with those vital literacy strategy developments.

We can have the best literacy strategy, with a polished 10-page policy, but all too easily it can get lost in the hubbub of a busy school term. Careful, well-crafted communication planning is essential to ensure that plans are picked up by everyone in school.

Read the rest of the series:

Leading Literacy…And Influencing Teachers

Leading Literacy…And Purposeful Professional Development

Comments