Metacognition is a well known term but perhaps less well understood for some busy teachers. Education Endowment Foundation guidance on the topic of 'Metacognition and Self-regulation' has always proven popular and now it is new and updated so it is well worth returning to explore.

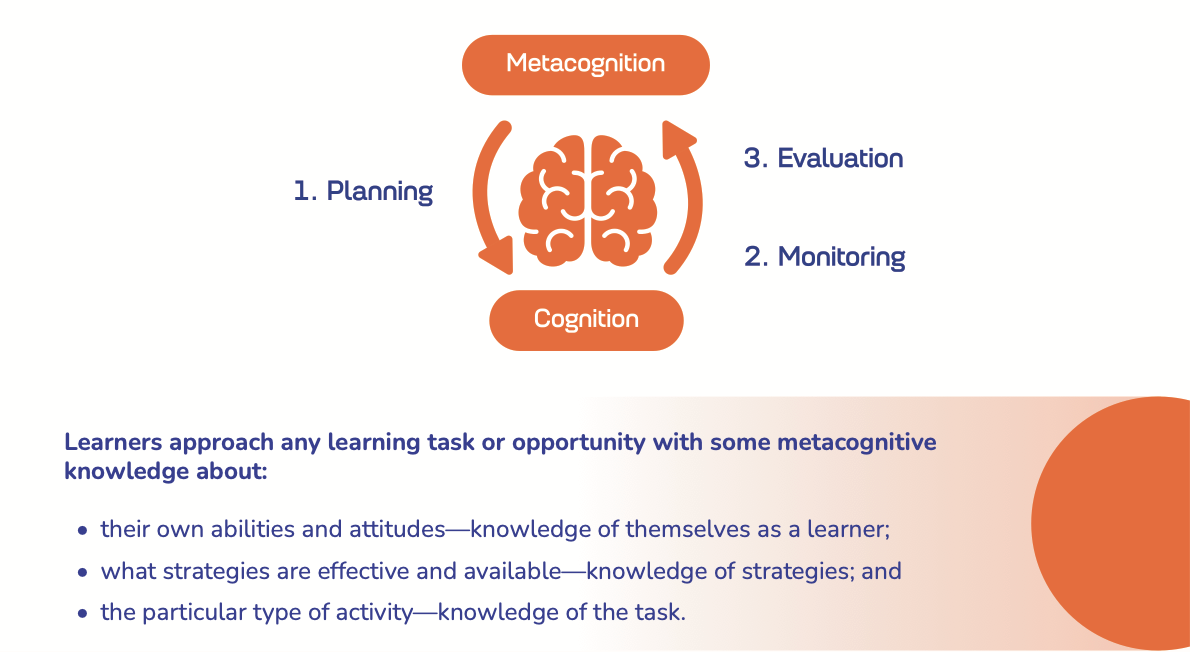

It is helpful to return to what metacognition is, and what it isn't, and how we might break it down to make useful guidance for busy teachers to enact in classrooms.

In concrete, everyday terms, we use metacognitive strategies all the time when we are undertaking most tricky tasks. For example, if you are travelling to a new venue for work, you put metacognitive strategies in place. You may plan to use a sat nav, or plan a bus route. You check and monitor timings. You may adjust for traffic or late trains. Then you are likely to evaluate whether you'll go the same route again in future.

The EEFs new and updated guidance report (find it HERE) has been updated by a great teams of authors (well done Beverley Jennings, Kirsten Mould and Corine Settle for authoring the newest update) and a team of expert reviewers. It is based on lots of of new research (over 355 studies).

The recommendations are similar to what they have been in the past, with more precise updates on different aspects of metacognition and self-regulated learning:

Metacognition is sometimes criticised for being tricky to pin down - and too multi-faceted to be actionable. It does require multiple recommendations, because it is complex, but that is because thinking and learning is complex and multi-faceted.

I do have sympathy with the notion of getting simple things right, such as getting students' attention and asking precise questions, or checking for understanding with precision, before tackling something like metacognition. However, it shouldn't be an either/or. Alongside getting the precise actions of teaching right, we must help student think, plan, check, evaluate, and take ownership of what they do, and this is the vital stuff of metacognition and self-regulated learning.

Metacognition becomes visible in the classroom if we identify and understand it more precisely. In maths, pupils are often talking non-routine problems that they need to plan, adopt strategies, trial them, adjust, and evaluate. Writing a story in English is full of planning - checking, editing and revising, then evaluating whether you did an effective job. Planning independent revision is crammed full of metacognitive strategies - or not so much for some students who don't manage the process well!

For young children, we may emphasise the self-regulation aspect of the guidance – from keeping calm, thinking and communicating effectively. For the distracted teenager, trying to stick at GCSE revision in a room bursting with distraction, we likely think similarly about the importance of self-regulation.

Understanding metacognition and self-regulation helps teachers understand how to help students navigate these challenges strategically and with metacognitive strategies. It is no silver bullet but it can help. There is substantive evidence that they offer the means to particularly support pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds.

I am also happy to see misconceptions about SEND addressed in the latest guidance update. Insights include:

"Some pupils, including some with SEND, will find self-regulation harder than their peers. Informed by a knowledge of their pupils, teachers may therefore provide additional modelling, adapt the metacognitive questions they ask, or take advice around how to support a pupil to self-regulate in class" (p6)

Metacognition is not some amorphous focus on fuzzy skills, but how we support students to plan extended writing in English, or scaffold planning in history, or evaluate their strategies in maths problem solving.

"There is little evidence of the benefit of teaching metacognitive strategies in generic ‘learning to learn’ or ‘thinking skills’ lessons. Instead, self-regulated learning and metacognition have often been found to be context-dependent—for example, good planning strategies in Key Stage 2 art may have significant differences to planning strategies in GCSE maths." (p35)

Professor Dan Willingham makes a compelling case that teachers need to have a working mental model of how children learn. I think guidance on metacognition and self-regulation can also help to build a clearer notion of how children plan, monitor and evaluate their learning - and it should be part of the working mental model of every teacher.

Do explore the new and updated guidance. New and updated tools will be coming soon too.

Comments