A version of this article was originally published in the excellent ‘Teach Secondary‘ magazine – you can subscribe HERE. It is well worth a read!

Controversies and complaints about spelling are centuries old. In his Preface to ‘A Dictionary of the English Language’, in 1755, Samuel Johnson derided writers for their “ignorance or negligence”. Today, the Internet is littered with spelling errors and would-be Johnson-types, correcting and chastising mistakes as they go. Amidst the ever-present debates, our students face one of the age-old renewals of emphasis on spelling, with it once more becoming a significant part of assessment at GCSE and highly prominent in the KS2 writing frameworks.

The English language is a dynamic and ever-changing thing: new words are coined daily, as well as archaic oddities littering our lexicon. You may ask, what chance do our students have of getting spelling right when they face over five hundred thousand words in the dictionary? Of course, they do face an uphill battle.

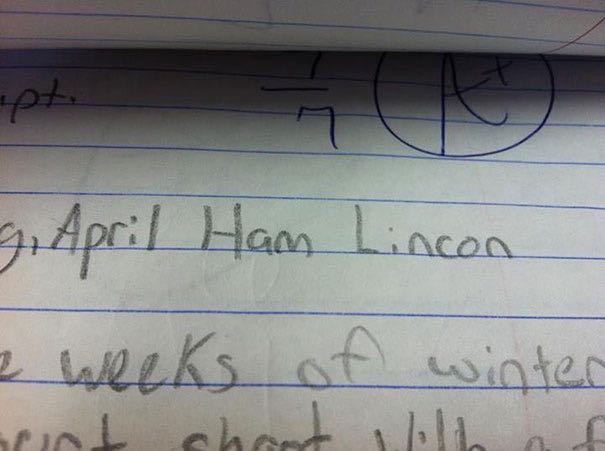

One of the significant issues with spelling standards is the way we go about teaching it in our schools. Dating back to a similar era as Samuel Johnson, our addiction to endless spelling lists has served our students badly. Armed solely with spelling lists for regular testing, we have for generations utilised a shallow and deficient method for teaching spelling.

The notion that ‘Look, cover, write, check’ is the default method for most children and teachers is a problematic one. It rests on the assumption that spelling can be visually memorised. Though this cue can prove somewhat helpful (it often needs significant repetition and ample existing word knowledge), it strains our students’ mental resources. We do not learn a language effectively by using lists, nor looking at the words and hoping they stick in our memory; ditto with spelling.

You may suggest a spell checker does the job, but then such tools cannot spot a homophone (to, too or two; poll and pole) and they commonly misjudge a significant number of errors, whilst not providing much learning for our students.

If we are to prepare our students to beat the examiners who are sticklers for spelling, and be prepared for life-long spelling accuracy, we need to take a deeper approach to learning words and their spelling patterns. We need to foster ‘word consciousness’. That is to say, an explicit awareness that words are richly connected, exist in families and exhibit common patterns (though few ‘spelling rules’ prove reliable – just scan the rule breakers for ‘An ‘i’ before ‘e’ after c’ for a start). In short, we need to connect spelling to the meaning of words.

As early as possible, we need to teach spelling as part of a rich, dynamic engagement with words. We need to help our students make sound connections, dig into the historical roots of words, and to seek out word parts, observing common prefixes and suffixes as a matter of habit as they write and proof-read.

Every subject domain has its essential vocabulary. Teachers should observe common word roots – ‘geo’ in Geography; ‘photo’ in Science – and explicitly highlight such connections and unveil their meaning. Word histories (etymology) can be fascinating and illuminating. Why does ghost have a silent ‘h’? Well, it is a five hundred year old mistake from a Dutch printer that is enshrined in our history!

Teachers can foster an awareness of spelling by focusing on word parts (the study of morphology), sharing the most common prefixes in the academic language of school, such as ‘dis-’, ‘un-’, ‘re-’ and ‘in-‘, noting words, observing patterns and even coining new, creative words.

Ultimately, we need to help our students find the meaning and patterns in spelling, deploying multiple strategies as they go. ‘Look, cover, write, check’ may be a start, but it must be accompanied by many other methods and a rich knowledge of words if we are going to help our students avoid ‘ignorance or negligence’.

Chapter 6 of my new book ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap’ is focused on spelling, entitled ‘We need to talk about spelling‘. You can order the book from Amazon HERE and Routledge HERE.

Comments