Illustrated by Ronald Searle, in Life Magazine, 1960.

Reading a classic novella like ‘A Christmas Carol’ is tricky for our teenage students. Yes, they have likely heard of Scrooge and seen a film adaptation or three, but when faced with the actual text and the world of the story, with its antiquated social context and complex vocabulary, it proves a difficult challenge.

After last teaching ‘A Christmas Carol’ seven years ago, I have the good luck to return to it this year. As I re-read the famous ghost story parable, text marking it ready for teaching, my young daughter commented how the words made the story nearly inscrutable to her (“I don’t understand – it’s really hard” were her precise words).

It is easy to recognise many of the more challenging terms in the novella, but when you take time to mark the text to find the difficult language you recognise the linguistic barriers students face. In the first few pages alone you encounter the complexity: from professional titles (“clergyman”, “clerk”, “chief mourner”, “sole executor” and “residuary legatee”), to sophisticated vocabulary for a religious readership (“unhallowed”, “solemnised”, “covetous old sinner” and “veneration”) and finally, just plain hard, unfamiliar words (“intimation”, “morose”, “impropriety”, “liberality”, “facetious” and “misanthropic”).

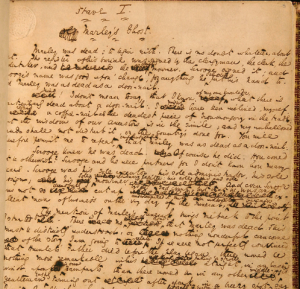

(The original hand written opening page of ‘A Christmas Carol’)

Identifying and pre-teaching the vocabulary in each of the five staves becomes essential to ensure students understand what they read. So, how do we best approach such a task? Simply giving students big lists of words will do little to aid their comprehension. We need to explicitly teach the Dickens’ world to help them form the foundations of knowledge wherein the vocabulary sits.

Clearly, Christmas, Scrooge’s parable and every scene in the story, is suffused with religious symbolism, language and meaning. In our more secular world, we can help our students understand the clear morality of the tale, whilst illuminating for them the lexical field of religion. Next, the story in situated in a harsh business world where Scrooge reduces humanity to surpluses and shillings; where the death of children was the norm. Establishing this context, with the horrid conditions suffered by many, provides another thematic hook to pin the challenging vocabulary onto.

By selecting larger social themes: religion, business, ghosts and the supernatural, powerful feelings and unique Victorian terms (a catch-all for the archaic language deployed by Dickens) you provide the required background knowledge to the text – what E.D. Hirsch describes as “mental velcro” – that can make the tricky vocabulary understandable.

When students are faced with lots of difficult words there can be a common sense of mental fatigue and sheer annoyance. We need to explicitly cultivate a sense of curiosity in the rich tapestry of words Dickens creates (or with any complex literary text for that matter). We can do this by unveiling the mystery of these seemingly alien words. By making connections and telling stories about words we can foster their interest and build their reading stamina.

Let’s take “unhallowed” from the “unhallowed hands” of the narrator on the very opening page of the tale. From the root word ‘hallow’ – meaning ‘to make holy or sacred’ (the Old English adjective ‘hâlgian’), we can hook this word into their knowledge of ‘Halloween’ or Harry Potter’s ‘Deathly Hallows’. We can link it to the roots of ‘holy’ and ‘halo’.

When students begin to develop a ‘word consciousness’ – that is to say an interest in the meaning and story of words – they can make more interesting inferences and uncover layers of latent meaning. In my opinion, it is important to foster this curiosity about words as a reading habit. By highlighting etymology, word roots, common pre-fixes and suffixes, we remove the obscuring veils that can inhibit the reading of our students.

Take the name ‘Ebenezer Scrooge’. The now famous name ‘Scrooge’ has become part of our daily lexicon, but the colloquialism ‘to scrouge’ meant to crush or screw. This fits neatly with the description of Scrooge in Stave 4 as an “old screw” – a slang term for a miser. The etymology of ‘Ebenezer’ has Hebrew origins – meaning ‘stone of help’. When placed together Ebenezer Scrooge is a clever oxymoron that represents the two sides of Scrooge’s character, before and after his visitations.

Interestingly, Dickens was a well-known perambulator (he regularly walked marathons around the streets of London) who plucked real names for his stories. His diaries record the name ‘Ebenezer Scroggie’ from Canongate Kirkyard graveyard, where Dickens mistakenly read Scroggie as a “mean man” and not a ‘meal man’ as it truly stated. This minor error made on a smog-filled evening may have birthed the most famous Christmas character and tale ever told!

Though our urge is to always ‘get through’ the book, it is the time taken to unpick the social context and to reveal the intriguing meaning behind the words of the story, which makes the experience more accessible, understandable and ultimately memorable for our students. For me, a priority is pre-teaching the world of the book and explicitly teaching vocabulary before students encounter the story itself.

As I plan for teaching ‘A Christmas Carol’, I am left considering general questions about my teaching for the year ahead:

- Am I fostering ‘word consciousness’ in my classroom?

- Am I explicitly teaching the background knowledge our students need to understand tricky texts?

- Am I explicitly teaching academic vocabulary and giving my students to tools to comprehend difficult texts, and make sophisticated inferences, when I cannot do it for them?

Useful resources for teaching ‘A Christmas Carol’

Given the privileged place for ‘A Christmas Carol’ in our culture, it isn’t hard to find useful resources online to help our students understand this literary classic. Here are just a few:

- The British Library has an excellent page – with a great video – to explore the origions of the text – see HERE. It also has an excellent essay on ‘Ghosts in A Christmas Carol’ – see HERE.

- The always useful ‘Victorian Web’ provides a useful introductory essay to the story HERE and it provides a handy article on ‘Dickens – ‘the man who invented Christmas’’ HERE.

- This Charles Dickens glossary is an handy littleguide to his lexicon that can begin to orientate students – see HERE.

- This essay by Dickens, called ‘What Christmas is as we grow older’ is a great pre-reading activity to understand his intent – see HERE.

Comments