As curriculum is complex, we routinely seek out a plethora of handy metaphors and analogies to make sense of it.

And so, in recent years curriculum has recently been described with a multitude of metaphors, such as a boxset (more Game of Thrones than the Simpsons), a voyage of exploration, or curriculum as narrative.

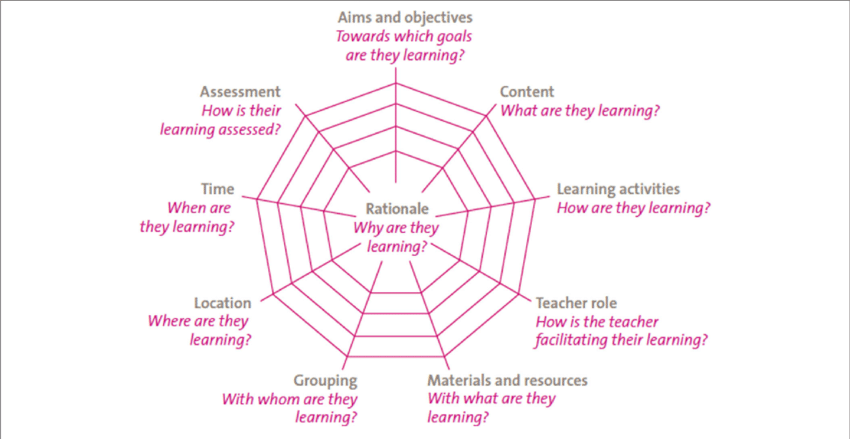

Each metaphor has explanatory value and helps bring some concreteness to what can too often prove a vague topic that is subject to contradictory theories and assumptions. Perhaps my favourite metaphor, outside of those already mentioned, from the curriculum theory of Jan van den Akker, is the ‘curriculum spiderweb‘.

The metaphor is apt primarily because a spiderweb is so intricately woven and interconnected, just like curriculum development. Done well, it is a beautiful result borne of effort and skill; however, like the natural spiderweb, it is also vulnerable, and its intricacies (subtleties of phase and subject, perhaps) can too easily be swept away by more powerful forces.

Van den Akker specifically marks out different facets of curriculum development and implementation in his spiderweb:

Jan van den Akker, Curriculum Landscapes and Trends (2003)

Though it can be helpful to limit notions of curriculum to the ‘what’ of the knowledge and skills that are to be taught, it does not encompass many meaningful related components that determine how such curriculum development is implemented in the classroom. Van den Akker gets us asking more questions of curriculum, revealing more interconnected threads of the spiderweb.

Exploring the threads of the curriculum spiderweb

Van den Akker specifies ten key components to curriculum development. These include a consideration of the values and principles that drive our curriculum decisions (the ‘rationale’ – or ‘intent’ in OFSTED parlance). Also, there are more broad organisational factors that are identified as important to our curriculum design, such as ‘time’ and ‘location’.

Van den Akker gets us to consider the substantive curriculum questions. And so, in terms of ‘time’, we are left with tricky practical questions, such as: how much time should be allocated to subject X in secondary school, or reading time in the primary school day? Are there financially driven timetable models in secondary that influence time? Different subjects will no doubt compete for curriculum time, with school leaders needing to understand the ‘content’ of the curriculum in great depth.

A consideration of ‘location’ is largely considered extraneous to the substance of curriculum. However, a primary school considering their use of forest school, or the school library, would surely beg to differ. Indeed, secondary schools no doubt think hard about how well pupils learn at home. Homework proves inextricably linked to how well we can implement the curriculum. For those secondary school subjects worried about curriculum ‘time’ – such as science and history (and more!) – then homework becomes yet more pressing.

‘Assessment’ is the critical bedfellow of curriculum, yet how well are we adapting our existing assessment systems as we shift the enacted curriculum? Schools have seen internal data assessments roundly critiqued, but attractive and manageable alternatives to existing data systems have proven less common. Does our internal assessment model match the demands of the curriculum change and the necessity to communicate progress to parents and governors etc?

I am not sure whether van den Akker has identified the ‘right’ ten components of curriculum development (I’d substitute ‘teacher role’ for ‘teacher development’ for a start), but the value of the metaphor is that it accurately represents the interconnectedness and multi-facetedness of curriculum development.

If it was simply a case of senior leaders getting out the way and tweaking the sequencing of curriculum content, then curriculum development would be a much simply, easier issue. It isn’t. The beautiful complexity of the spiderweb captures some of the difficulty and rewards that we can gain from a focus on curriculum change.

Comments