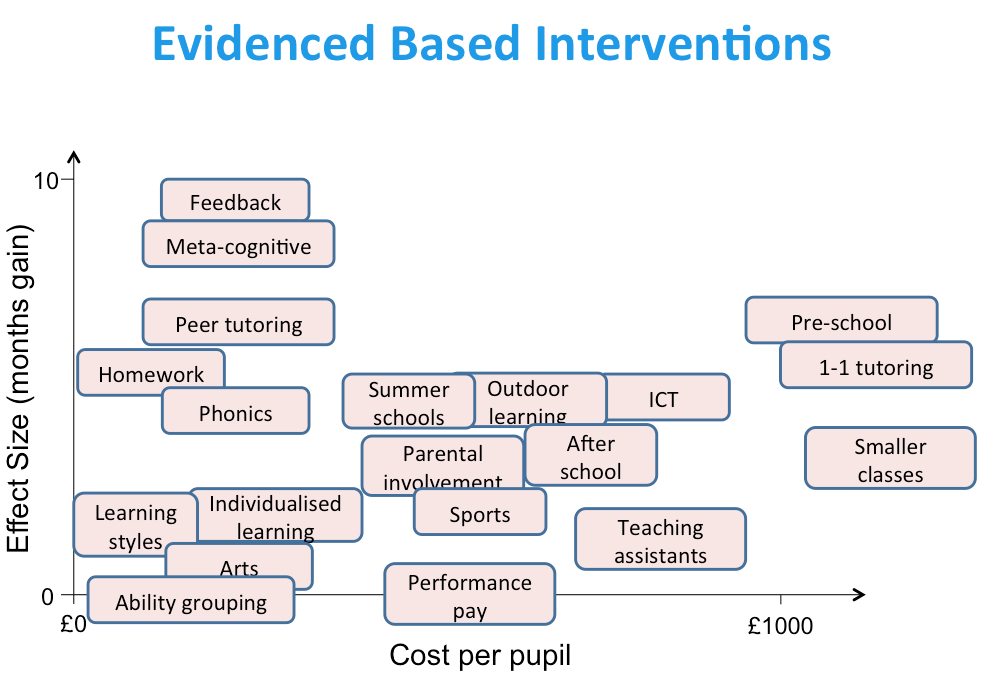

I’ve always held with the Beatles lyric that we get by with a little help from our friends. In classrooms, with students learning and helping one another learn, it can often help too (when done well). The evidence to support the effectiveness of ‘Peer Tutoring’ programmes in schools has always been strong and I have confidently promoted such approaches myself. This last week, the ‘Education Endowment Foundation’ (EEF) has reported on two projects on peer tutoring, revealing poor results for both and raising the spectre of the potential pitfalls with this approach.

Peer tutoring has proved popular in schools for many reasons. For one, it offers up time for more individualized learning for students. It builds upon the expert instruction of the teacher, but of course, the teacher cannot have one-to-one time with all students, therefore, well structured peer tutoring can supplement high quality teaching, offering peers more feedback, in language that they understand.

The pitfalls with this ideal scenario? We know from research from Graham Nuthall that most of the feedback students get is from their peers (something like 80%), but, alas, most of it is wrong! Peer tutoring offers the opportunity to better structure the feedback students receive, though, without thorough formative checking of that very feedback, the opportunity may not be exploited. Any peer tutoring should obviously be carefully constructed and it requires good quality training for students to do it well.

As the EEF studies show, even this may not prove enough.

We know from existing evidence that the process of teaching others can benefit the tutor as much as the tutee. It is a trick employed by teachers everywhere. Why? Well, peer tutoring forces students to organize and structure their thinking very actively. They have to devise their own explanations and analogies etc., which may deepen and reinforce their own understanding. Perhaps the motivation of an audience can help too.

There are hidden attendant benefits too: the teacher can be freed up to undertake whatever teaching they see fit, such as the opportunity to work with those students who are struggling most, whilst the rest of the class engage in the structured peer tutoring.

The EEF RCT report on ‘Paired Reading’ – see the report findings here – is a very typical example of peer tutoring. Students from Year 9 are trained (such as how to give praise and positive reinforcement etc.) to support Year 7 readers in a paired reading programme. The sixteen 30 minute sessions were conducted over a period of months in timetabled lesson time. There proved to be no positive impact on reading attainment when students were tested, despite the training and time given over to the programme.

Crucially, lesson time was given over to these half hour sessions, so such a commitment to any one teaching and learning approach needs wise judgment. This evidence should no doubt give us pause. At Huntington School we conduct a paired reading programme, but it is held in form time, so we are not effectively ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’ in terms of academic reading, and teaching time is not lost. Any studies seeking to replicate peer tutoring really needs to precisely consider the ‘when’ as much as the ‘how’. Equivalent ‘reading lessons’ have been employed at Huntington and in many other schools. Though we value reading reading for pleasure hugely, such independent reading doesn’t neccessarily enhance their reading skill, nor provide them with the knowledge to develop their understanding.

Interestingly, the ‘Paired Reading’ programme shares many similarities with the many ‘reading for pleasure’ studies (such as the ‘Chatterbooks’ study) that have time and again failed to have an impact on reading attainment in EEF trials. The problem, as I see it, with the ‘Paired Reading’ peer tutoring programme is that is may encourage reading for pleasure, but it offers up no systematic reading strategies, nor any obvious ways for giving students the knowledge and skills in reading that they need to improve. If we compare the metacognition reports from the EEF, we see a structured approach to developing writing skills that can be applied more systematically and effectively.

Useful information for teachers and school leaders:

– Peer tutoring does necessitate structured support and training, for both teachers and students, but even that investment is no guarantee of success. There are no silver bullets, even when the evidence gives us useful ‘best bets’.

– Undertaking peer tutoring programmes during lesson time, when they could be viably undertaken at other times, such as in form/registration time, could likely to dilute the impact of the intervention – particularly with a trial that effectively seeks to gauge whether more structured reading improves reading in attainment. Given the ‘Paired Reading’ programme is undertaken during lesson time, this may have hampered its impact.

– Any peer tutoring programme for reading needs an explicit emphasis on developing structured reading support that gives students the tools to read more effectively. Reading strategies, comprehension strategies and vocabulary building strategies can all be reinforced through peer tutoring. If these are taught and then also reinforced and used in typical classroom instruction then the likelihood of their impact surely grows.

– Self-selecting reading books and simply a little ‘more’ reading is unlikely to have a cumulative effect that sees better reading attainment in a relatively short term (reading for pleasure likely has discernible impact, but over a much longer time span).

– Reading for pleasure is a desired outcome from schooling, but it is not in and of itself a means to improve reading attainment, especially for those students who have considerable barriers to their reading.

– We should focus on the attainment outcomes garnered from the tutoring itself, but we should not ignore the gains often implicit in such approaches. The social skills and personal self-confidence in academic contexts that can emerge through such approaches should not be ignored. Such confidence matters and is to be valued alongside academic outcomes.

– The tutor often gains as much from the programme as the tutee and this is sometimes missed in research evidence.

– In lesson time, outside of more controlled programmes, such reciprocal teaching can prove a useful teaching approach for a teacher seeking out some variety from their direct instruction.

In interpreting the evidence for this paired reading programme, I haven’t lost faith in the potential power of peer tutoring. Instead, I think indicates that the ‘what’ and ‘when’ of successful peer tutoring is essential. Though training students for peer tutoring is an essential prerequisite, what you train them to tutor obviously needs to be just right. Put simply, I don’t think that ‘Paired Reading’ is the best approach to improve reading outcomes.

A good study to challenge the evidence of this particular project would be to undertake peer tutoring on a similar time scale, outside of lesson time, in morning form time for example, with a more explicit selection of texts (ensuring you have fully supported the knowledge of the tutor for each respective text) and a more focused emphasis on reading strategies and specific vocabulary comprehension strategies. This could be integrated and aligned with teacher instruction that reinforced the same reading strategies.

Sometimes sure-fire strategies are proven to miss the mark, like peer tutoring here, but learning what doesn’t work may prove to be just as powerful as learning what does.

Comments