It is a truth universally acknowledged, that vocabulary knowledge is crucial for pupils’ school success. Pupils are language sponges, learning thousands of words each year. Like increases in a child’s height, it is a slow but inexorable development. On a daily basis it is near-imperceptible, but when you begin to count the passing of school terms, you can see significant differences occurring. For teachers, the key question is how can you best enhance and enrich pupils’ vocabulary.

For busy teachers, digging into the research on vocabulary development and language gaps can prove daunting. It is helpful to distil that wealth into consistent pillars of practice that are ‘best bets’ for supporting, and super-charging, vocabulary development:

The Three Pillars of Vocabulary Teaching

1. Explicit vocabulary teaching

2. Incidental vocabulary learning

3. Cultivating ‘word consciousness’

Explicit vocabulary teaching

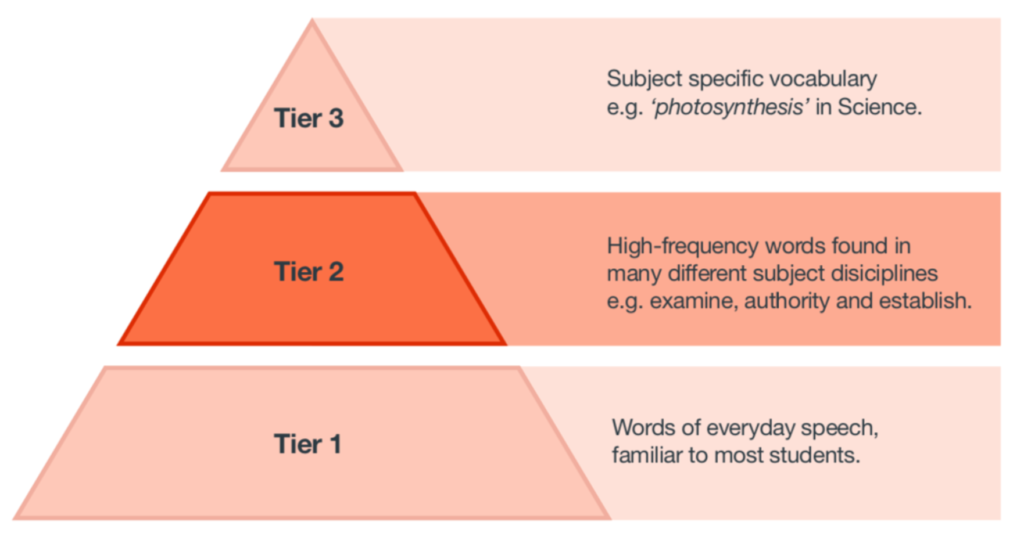

Explicit vocabulary teaching can provide a vital boost to our pupils’ vocabulary development. In recent years, building on the excellent research from Beck, McKeown and Kucan, awareness of choosing the right words to teach has become more common across primary and secondary schools – such as their popular ‘Tiers of vocabulary’ model:

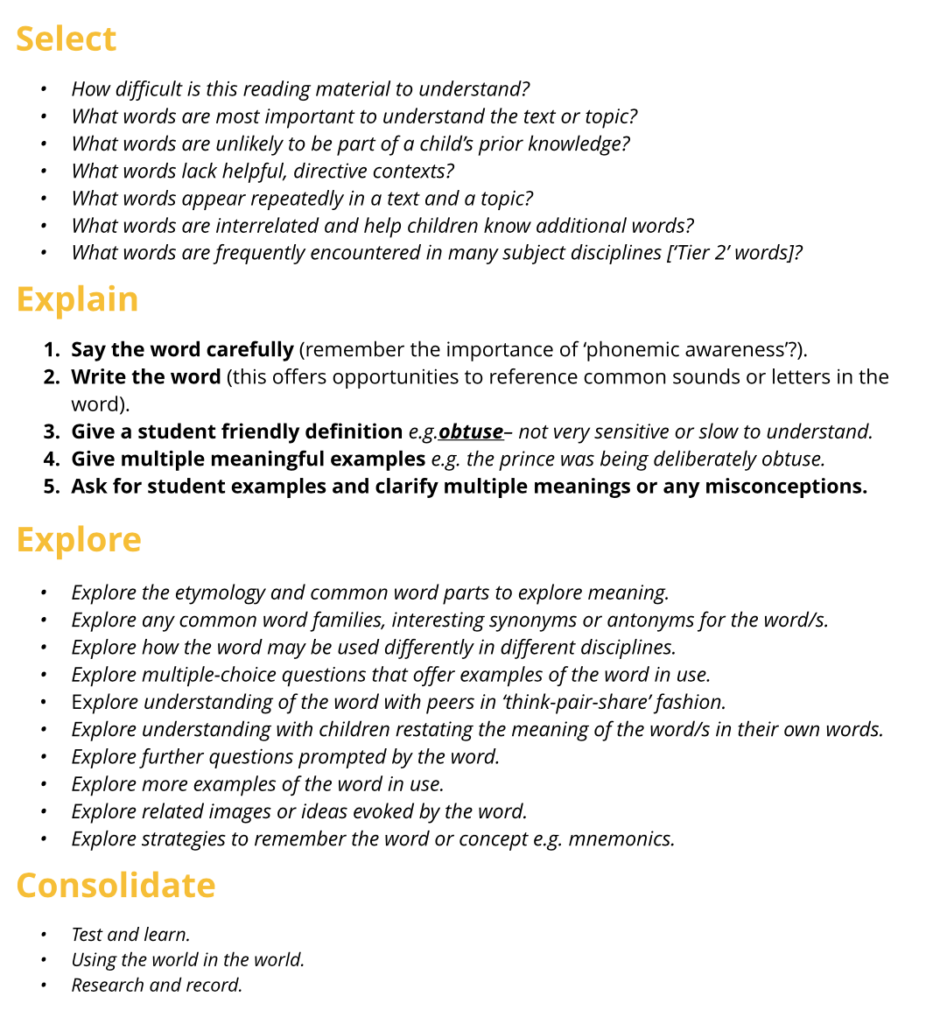

This awareness of choosing vocabulary to be learnt, making rich connections that build pupils’ vocabulary schemas (networks of well connected links), has been bolstered by practical approaches to teaching these individual words and phrases, such as my SEEC model (influenced the work of brilliant researchers, such as Robert Marzano, Isabel Beck and colleagues):

We know that teaching complex academic concepts clothed in sophisticated vocabulary proves a barrier to too many pupils. Dishing pupils a dictionary won’t necessarily lead to successful learning. And so, careful attention to aligning the curriculum with opportunities for explicit vocabulary teaching can unlock academic challenges, such as understanding the process of photosynthesis in biology, or learning about the Great Fire of London in key stage 1.

The rise of ‘knowledge organisers‘, and similar tools, offer opportunities to identify key vocabulary, but we should be wary of assuming stacking vocabulary in a list for some quick quizzing offers anything like the deep understanding and rich connections pupils need to make between words, phrases, concepts and big ideas. More active approaches to teaching and engaging pupils with new words include Frayer Models, ‘word ladders’ (see p10), words maps, word gradients, and similar.

It can be helpful to consider ‘keystone vocabulary‘ to identify those vocabulary choices that offer pupils opportunities to generate meaningful links via their talk, writing, reading and more. For example, when I have taught romantic poetry to year 7s in the past, we identified important ‘keystone’ nouns that unpacked a lot of the big ideas that underpin Wordsworth’s poem about daffodils:

Now, you can rightly debate whether these are the right words to teach (it is excellent professional development to discuss these small but often crucially significant building blocks of knowledge), but the explicit attention to these words can offer a foundational understanding of what is an unfamiliar word. It is a schema that pupils can add to and go onto make many surprising, exciting connections as they go onto read the poems selected.

““All words are not valued equally. Instead, what we want children to learn is the language of school. For many children, this is a foreign language.” (p. 68).

Stahl and Stahl (2004)

Incidental vocabulary learning

You cannot explicitly teach all the words! With over a million words in the English language, teachers make careful selections regarding subject specific vocabulary and those sophisticated Tier 2 words. It is clear that reading rich texts, both in the classroom and beyond the school gates, is critical for language and vocabulary development. Put simply, the more words you read, the more you learn.

When reading complex texts, pupils can struggle to learn new, unfamiliar words, so helping pupils with strategies to notice and record interesting vocabulary is likely to prove valuable. It may be having pupils keep a ‘word hoard’ of their own – or use vocabulary book marks – or simply record words in the back of their books, for discussion and questioning later. Setting up a ‘classroom dictionary’ in domains like geography, science or maths, could help move the incidental learning to something more intentional.

Teachers need to flood the classroom with vocabulary alongside explicit teaching. Putting in lots of reading miles on the clock really matters to maximising vocabulary learning, so well structured daily reading opportunities (with care taken over reading choices) can grow pupils’ vocabulary, though it may not be immediately visible (remember that opening analogy of height and daily growth?).

When teachers talk about words – their subtleties, misnomers, histories, and more – building on reading high quality texts, these conversational turns unlock important shades of meaning for pupils that can fend off misconceptions and lead to greater understanding when reading. Many of these opportunities will arise spontaneously. You simply cannot predict all the words pupils will know and not know. However, with awareness that some of these ‘teachable moments’ could be missed, we should aim to wed incidental learning to explicit teaching.

Cultivating ‘word consciousness’

‘Word consciousness’ is an “awareness and interest in words and their meanings” (put a little more interestingly, it is pupils “bumping into spicy, tasty words that catch your tongue”). This love of language and continual curiosity about what words mean, where they are from, and their legion of connections, feels like the end-game of great vocabulary teaching. With careful cultivation, this curiosity can be fostered and it can help fuel our pupils’ school success.

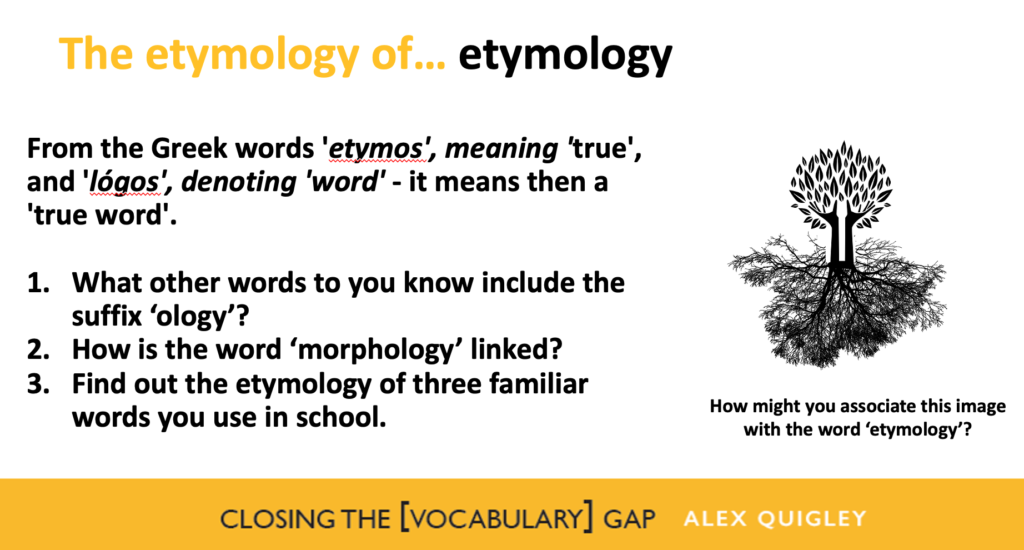

The teaching of word parts (morphology) and word histories (etymology) are some of most well-evidenced methods of explicit vocabulary teaching, but done well, we hand over the baton to our pupils and they become ‘word conscious’, spying word parts and word families each time they read, talk and write. Faced with a complex word like ‘oligarchy’, pupils can recognise the familiar root ‘-archy’, meaning ‘rulership’. It offers an essential hook to understand the word, offering more familiar related words like ‘monarchy’.

Common practices, such as ‘interactive word walls’, ‘word of the week’, and similar, can engage pupils and reach out to parents. We should be wary these are not superficial gimmicks and that robust vocabulary teaching is careful crafted in curriculum choices and sustained teaching practices too.

What marks out ‘word consciousness’ from explicit teaching and incidental vocabulary learning? For me, it is the focus on gifting our pupils with independent word learning strategies. It is the understanding about the richness of words that ensures that incidental word learning happens more effectively. It is the end goal, and means, for continued vocabulary development.

“Education is the process of preparing us for the big world and the big world has big words. The more big words I know, the better I will survive in it. Because there are hundreds of thousands of big words in English, I cannot learn them all. But this does not mean that I shouldn’t try to learn some.”

David Crystal, ‘Words, Words, Words’

Related:

If you are interested in vocabulary development, my book ‘Closing the Vocabulary Gap‘ is available here (Amazon) and here (Routledge).

Comments