They say that interests and trends in education come and go in cycles. Depending on your attitude, it beckons the disagreeable return of a fad, or it is the timely return of a vital aspect of education. ‘Oracy’ is one of those touchstone trends that comes and goes in cyclical fashion.

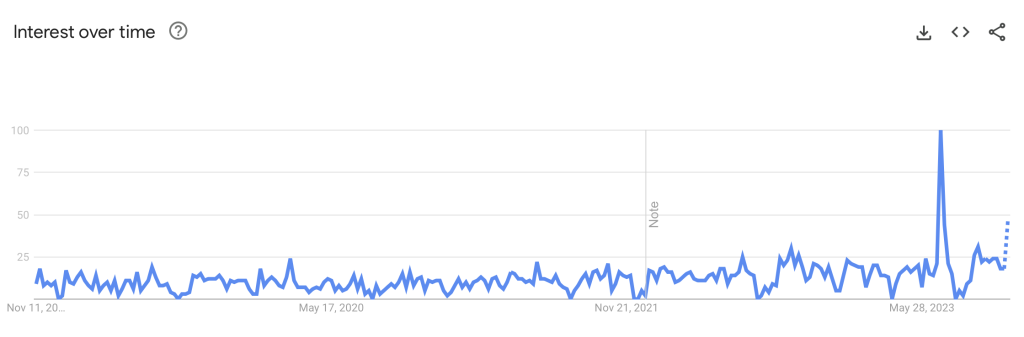

In 2023, oracy appears to be back on the agenda. With the term making it into speeches by Keir Starmer, or various policy think pieces, political interest in oracy is reborn. Google searches in the UK spiked as a result:

The problem with oracy, like many terms in education, is that it elicits many different interpretations. Well-meaning politicians may have different conceptions of it from busy teachers. With different interpretations can come disagreement and even confusion.

So, what is oracy anyway?

The term was first termed by the academic, Andrew Wilkinson, in the 1960s, with a big ‘O’, in a direct attempt to promote its importance, in relation to the prioritisation given over to ‘literacy’ and ‘numeracy’. Experts in the field describe oracy similarly, but in different ways too:

“[Oracy] is what the school does to support the development of children’s capacity to use speech to express their thoughts and communicate with others, in education and in life.”

Robin Alexander (2012), ‘Improving Oracy and Classroom Talk in English Schools: Achievements and Challenges’

“[Oracy] really represents the set of talk skills that children, that people, should develop, in the same way that we would expect people to develop reading and writing skills […and] sums up that teachable set of competencies to do with spoken language.”

Neil Mercer, from ‘The State of Speaking in Our Schools’

The Education Endowment Foundation explores Oral language approaches as including:

- “Targeted reading aloud and book discussion with young children;

- Explicitly extending pupils’ spoken vocabulary;

- The use of structured questioning to develop reading comprehension; and

- The use of purposeful, curriculum-focused, dialogue and interaction.”

EEF Toolkit, Oral Language Interventions

There are no shortage of definitions, descriptions, and practices, that attend oracy. The problem is obvious: with so much variation, there can be a lack of clarity. The National Curriculum uses ‘spoken language’, but so many other terms are used interchangeably too: talk, oral development, communication skills, speaking and listening, dialogic talk, academic talk, reasoning, ‘sustained shared thinking’, ‘high quality interactions’ and much more.

Of course, oracy means something different in early years than what it means in the secondary school classroom, though we may use the term interchangeably in a host of different contexts.

Robin Alexander describes the tricky issue with ‘oracy’ that, “talk is the one area of classroom learning where the familiar distinctions between what and how, content and process, curriculum and pedagogy, break down”. As a result, if we are not careful, oracy could describe everything in the classroom and, therefore, nothing will change.

If oracy is going to prove a trend that makes a positive difference, or not, to teaching and learning across schools, then clarity will matter. Definitions, principles, and practices, will need to be clear. Otherwise, we’ll defer to habits, assumptions, stereotypes, and even end up in arguments.

You can see in oral language interventions for young children like NELI (The Nuffield Early Language Intervention), that oracy can lead to educational success – particularly for disadvantaged pupils. But classroom practices are often not so tightly defined. As a result, if oracy as policy is to translate into anything, then teachers need support to develop clear parameters for good argumentation in the English classroom, or effective reasoning in mathematics.

Teachers routinely make hundreds of choices about oracy every week in their classrooms. While that classroom door is shut, and teaching and learning is happening, those choices are seldom influenced by national policies or Google search terms.

Should teachers ‘do’ oracy? Well, we first need to have a shared answer to the question: ‘what is oracy anyway?’.

Some valuable freely available sources of further reading include:

- ‘Oracy: The State of Speaking in Our Schools’, by Will Millard and Loic Menzies. A really useful report which gives a good background to the debates and practices in schools.

- ‘Improving Oracy and Classroom Talk: Achievements and Challenges’, by Robin Alexander. A great background to the policy history of oracy.

- ‘Evidence into Action EEF Podcast: High Quality Talk’. This podcast includes Neil Mercer, who gives a great background to oracy and its role.

- Oracy Cambridge – blog series. Oracy Cambridge have a range of blogs that go some way to help teachers understand what oracy is and what it isn’t.

Comments