If you are a school teacher and you haven’t heard of Carol Dweck’s ubiquitous growth and fixed mindset concept then… quite frankly, where the hell have you been for the past few years?

No doubt lots of good has emerged from this common-sense psychological framework, with a few dodgy approaches too. The growing evidence base, showing the limitations, flaws and best bets relating to these popular psychological interventions, is important to help improve what we do in schools.

More recent evidence related to growth mindset interventions is emerging – developing our knowledge and adapting our practice. Only this week, the Education Endowment Foundation published its Changing Mindsets EEF report, based on the trial conducted by the University of Portsmouth. It reveals some really interesting insights. Please do read the report yourself, but I did find some of the findings interesting and worthy of further discussion:

– Clearly, the interventions aimed at training the students, helping them understand about a growth mindset, brain plasticity etc. had more of a positive impact than the intervention aimed at training teachers. Relevance for schools: Attempting to change the life-long attitudes of teachers may prove a fool’s errand. Better to attempt to directly change the attitudes of students who, ultimately, are the captain of their own learning. Growth mindset interventions will likely best benefit those students who need to better self-regulate their learning.

– I would hypothesise a couple of teacher INSET training sessions, however useful, are simply not going to change teacher beliefs and habits in any meaningful way, no matter how potent the message. Relevance for schools: one off INSET training for ‘growth mindset’, or whatever aspect of teacher practice, rarely changes teacher habits. CPD only works when it is sustained over time, supported by school structures, whilst being embedded into the fabric of planning and training in a series of sessions focused on teaching and learning and student outcomes.

– “Intervention and control schools were already using some aspects of the growth mindsets approach. This may have weakened any impact of the interventions.” Relevance for schools: given that growth mindset is now pretty much common knowledge in schools, it is tricky to fairly evaluate interventions. Not only that, but schools struggle to evaluate with anything like the controls of a independent study like this one. Still, we can surely evaluate better and ask questions about our interventions, being honest when their impact is negligible.

There were some positive findings of two months gain in learning relative to those students who didn’t receive the growth mindset message intervention. Overall though, there is doubt that the results showed definitive statistical significance. That is to say that the growth mindset interventions may not be the cause of the improvement made by students of a couple of months. Still, given the relatively light intervention (six short sessions on study skills with a growth mindset emphasis – in comparison with a control group who had the equivalent sessions, but on general study skills), it provides us with enough reason to further pursue ‘growth mindset interventions’. Relevance for schools: Psychological interventions can be slippy things. Finding a ‘growth mindset attitude’ as being the direct cause of improvements in student attainment is no doubt tricky, but as such interventions can prove very quick, cheap and easy, then we don’t stand to lose much in the pursuit. Investing too much time and money in ‘growth mindset programmes’ won’t likely prove a silver bullet – as research has found: ‘they are not magic‘. Perhaps then better stealthy, short interventions are the best bet.

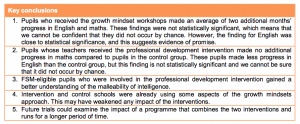

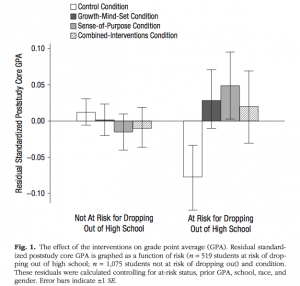

‘Changing Mindsets‘ key conclusions:

The data findings are helpfully broken down into sub-groups:

This ‘Changing Mindsets‘ study isn’t the only recent growth mindset orientated research. The study, ‘Mind-Set Interventions Are a Scalable Treatment for Academic Underachievement’, by Paunesku, Walton, Romero, Smith, Yeager, Dweck (2015), has also shown promise regarding the impact and scalability for growth mindset focused interventions. Some of the messages are similar to the study above: both were student focused interventions; they were both relatively short interventions (though the Dweck study used technology); they both focused on the message that intelligence is malleable etc.

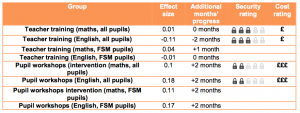

The striking focus of the Dweck study was that students ‘at risk of dropping out of high schools’ benefitted much more from the interventions:

Now, both studies recognise their limitations and, like most good research, they recommend replication, better future studies that stand on their shoulders and testing their findings in different contexts. My view: the message of the malleability of the human brain and the power of effort and resilience is, as the Americans would say, a no brainer. How we convey that message, however, may need work and some subtle design and application. Quick, well targeted and stealthy growth mindset interventions may well prove our best bet given the growing evidence.

Related reading:

– I have written here about some of the problems that attend growth mindset: The Problem with Growth Mindset

– I think we can better embed growth mindset principles into teaching and learning. I think twinning it with metacognition is key: Growth Mindset – SO What’s Next?

– Considering what ‘stealthy psychological interventions’ might look like? Give this a read: Successful Learning by Stealth

Comments